Print Friendly

Special Considerations in Diagnosing and Treating ADHD

Part 3: Adults

Sharon Wigal, PhD

Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of California, Irvine

Timothy Wigal, PhD

Associate Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University

of California, Irvine

This CME activity is now expired. Please visit www.psychiatryweekly.com to view current activities.

This is the third in a 3-part Psychiatry Weekly CME series on special considerations in diagnosing and treating

ADHD. Parts 1 and 2 focused

on the preschool-age population, and the child and adolescent population, respectively.

Accreditation Statement

This activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essentials and Standards of the Accreditation Council

for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and MBL Communications,

Inc. The Mount Sinai School of Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation

The Mount Sinai School of Medicine designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM.

Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Faculty Disclosure Policy Statement

It is the policy of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine to ensure objectivity, balance, independence, transparency, and

scientific rigor in all CME-sponsored educational activities. All faculty participating in the planning or implementation

of a sponsored activity are expected to disclose to the audience any relevant financial relationships and to assist in

resolving any conflict of interest that may arise from the relationship. Presenters must also make a meaningful disclosure

to the audience of their discussions of unlabeled or unapproved drugs or devices.

This activity has been peer reviewed and approved by Eric Hollander, MD, Professor of Psychiatry and Chair at Mount Sinai

School of Medicine. Review Date: May 31, 2007

Statement of Need

6%–9% of children are estimated to have ADHD, and 65%–85% of children with ADHD continue to meet at least

some criteria for ADHD and present with significant impairment as adults. Of the estimated 4%–5% of adults with ADHD,

only 20% are ever diagnosed. Recognition in this patient population is complicated by the dominance of inattentive symptoms

(which are less likely to draw notice than hyperactive symptoms). Diagnosis is complicated both by the difficulty of obtaining

reliable information on symptoms from early childhood, and the high prevalence of comorbidities.

Common comorbidities include substance abuse, mood disorders, and anxiety disorders, all of which significantly impact

a patient’s quality of life and can contribute to the overall impairment of adults with ADHD, who earn less money,

experience more difficulty at work, and change jobs more often than adults without ADHD. Psychosocial and pharmacologic

treatment are both used, and the latter is predominantly stimulants, though one non-stimulant medication has been FDA approved

for this patient population.

An important educational need exists to refine the diagnostic and treatment strategies of clinicians treating adult patients

with ADHD. Particularly in light of the significant impairment caused by ADHD, effort must be made to increase recognition

among this patient population. Clinicians must also keep abreast of emerging data on treatment efficacy.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the impact of ADHD in the adult population, and the role of comorbid disorders in diagnosis, impairment, and

treatment response.

- Assess treatment options for adults with ADHD.

- Explain the difficulties in diagnosing this patient population, and be aware

of diagnostic strategies designed to counter these difficulties.

Target Audience

This activity will benefit psychiatrists, hospital staff physicians, and office-based “attending” physicians

from the community.

Funding/Support

This activity is supported by an educational grant from Shire.

Faculty Disclosures

Sharon Wigal, PhD, has disclosed that she has received research support from Cephalon, Eli Lilly, McNeil,

New Rivers, NIH, and Shire; has served as an advisor or consultant to Cephalon, McNeil, New Rivers, Novartis, Shire, and

UCB; and has served on the speaker’s bureau for McNeil, Shire, and UCB.

Timothy Wigal, PhD, has disclosed that he has received research support from Cephalon, Eli Lilly, McNeil,

New Rivers, NIH, Novartis, and Shire; has served as a consultant or advisor to McNeil, Novartis, and Shire; and has served

on the speaker’s bureau of McNeil and Shire.

Peer Reviewers

Eric Hollander, MD, reports no affiliation with or financial interest in any organization that may pose

a conflict of interest

Daniel Stewart, MD, PhD, reports no affiliation with or financial interest in any organization that may

pose a conflict of interest.

To Receive Credit for this Activity

Read this poster, reflect on the information presented, and then complete the CME quiz found in the accompanying brochure

or online (www.mssmtv.org/psychweekly). To obtain credit you should score 70% or better. The estimated time to complete this

activity is 1 hour.

Release Date: July 9, 2007

Termination Date: July 9, 2009

Introduction/Prevalence

65%-85% of children with ADHD continue to meet at least some of the criteria for ADHD and present with impairment related

to primary symptoms of the disorder as adults.1 Evidence indicates that 4%-5% of adults have ADHD and that <20%

of them are diagnosed.2 Presentation in adults is heavily biased toward inattentive symptoms,3 which

are less likely to draw notice than hyperactive or impulsive symptoms and may contribute to the under-recognition of ADHD

in this patient population. Diagnosis is complicated both by the necessity of demonstrating symptom onset prior to 7 years

of age and by the prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in adults with ADHD; anxiety disorders and substance abuse

are particularly prevalent in this population.4 Identifying comorbid disorders in ADHD is particularly important

as they can interfere with diagnosis and complicate treatment. Symptoms of ADHD can severely impact an adult’s life;

the disorder is implicated in more frequent job changes, more martial discord, and decreased quality of life.

Presentation and Impact

Male children are far more

likely to be diagnosed with ADHD than female children; by late adolescence and

adulthood the ratio has shrunk from 3:1 to 1:1.6,7 This may be due

to the predominance of hyperactivity in male children with ADHD and the

diminution of hyperactive symptoms across individuals with ADHD as they age

(hyperactive symptoms are generally easier to spot than inattentive symptoms).

ADHD may manifest differently in females than males, but more research is

needed to clarify gender-related issues in diagnosis, treatment, and the impact

of ADHD symptoms on life events. Adult males with ADHD earn less money,

experience more difficulty at work, and change jobs more often than adult males

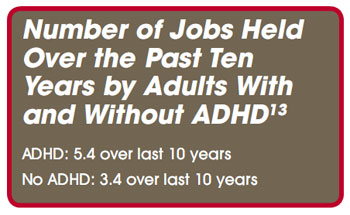

without ADHD.8 Adults diagnosed with ADHD also have, on average,

fewer years of education and are less likely to be professionally employed.9

Other studies have indicated

that patients with substance use disorders and ADHD are more prone to social

maladjustment, lower levels of work-related achievement, and higher rates of

separation and divorce than are patients with substance use disorders without

comorbid ADHD.10,11 There is also evidence that adults with ADHD are

more likely to report psychological maladjustment and to have more speeding

violations than adults without ADHD.12 Adults with ADHD also report

less satisfaction in the workplace and in life in general.13

Other studies have indicated

that patients with substance use disorders and ADHD are more prone to social

maladjustment, lower levels of work-related achievement, and higher rates of

separation and divorce than are patients with substance use disorders without

comorbid ADHD.10,11 There is also evidence that adults with ADHD are

more likely to report psychological maladjustment and to have more speeding

violations than adults without ADHD.12 Adults with ADHD also report

less satisfaction in the workplace and in life in general.13

Adults

with ADHD may have developed effective coping skills over the years, but they

tend to have difficulty with time management, sleeping, motivation, and tolerating

frustration. They are also prone to talking too much and/or too fast at work

and in social situations. They are likely to seek help when managing the

demands of work and/or home life become overwhelming.14-16

Comorbidity

Comorbid disorders are

common in adults with ADHD. Anxiety disorders, substance abuse disorders, and

mood disorders are all highly prevalent comorbidities in this patient

population, and there is also a significant incidence of antisocial disorder.

Substance Use Disorders

Substance

use disorders tend to manifest in adolescence or early adulthood and affect

15%-20% of adults in the US.20 There is significant bi-directional

overlap between ADHD and substance-use disorders; 40%-50% of adults with ADHD

present with comorbid substance abuse, and 15%-25% of adults with substance use

disorders present with comorbid ADHD. Marijuana is the most common substance

abused by adults with ADHD, although alcohol abuse is also common.21

Substance

use disorders have a significant impact on the long-term course of ADHD; not

only are patients with ADHD and comorbid substance abuse more likely to have

another psychiatric disorder, but patients with ADHD and comorbid substance

abuse have been found to have an earlier onset of symptoms, longer course and

greater severity of disease, and more relapses. ADHD has also been linked with

increased risk of cigarette use and increased difficulty in quitting smoking.21

The latter may be due in part to nicotine’s reducing ADHD symptoms.22 Early

treatment with stimulants may decrease the risk for later development of

substance use disorders, particularly when adolescents maintain pharmacotherapy.23

First-line treatment for adults with ADHD and recently resolved substance abuse

may include atomoxetine or strongly noradrenergic TCAs, due to their lack of a

dopaminergic effect, and stimulants with decreased liability for abuse.24

Depression

Up to

50% of adults with ADHD will experience at least one depressive episode during

their lifetime,25 with up to 35% suffering from major depression.26

There is evidence that patients with comorbid ADHD and depression respond well

to antidepressants but do not respond as well to treatments for ADHD as do

patients with ADHD without comorbid depression.27 Thus, clinicians

may consider attempting to treat the depression before prescribing stimulants

in patients with comorbid ADHD and depression.28 If treating both

disorders simultaneously, MAOIs must not be prescribed with stimulants due to

the possibility of hypertensive crisis.29 Overall, practitioners

must exercise caution when prescribing stimulants and TCAs in combination due

to the product labeling contraindication, although research suggests the

combination is generally safe.30

Bipolar Disorder

Approximately

10%-15% of adults with ADHD co-present with bipolar disorder, and males are

more likely than females to present with both disorders. The disorders are

further linked in that the onset of mood disorder in patients with comorbid

ADHD and bipolar disorder predates the onset of mood disorder in patients

without ADHD by an average of 5 years. Comorbid ADHD and bipolar

disorder have also been linked to increased severity of bipolar disorder.31

Other Comorbid Disorders

Comorbid

anxiety disorder is highly prevalent in adults with ADHD, but evidence of the

interaction of anxiety with ADHD is unclear. There is some indication that

adults with comorbid ADHD and an anxiety disorder have more pronounced

attentional deficits.31 In addition, studies have shown that ADHD in

adults is strongly associated with sleep disturbance,32 but it is

not clear whether actual sleep disorders are linked with adult ADHD. Poor sleep

patterns contribute to a worsening of ADHD symptoms in adults, and stimulant

treatment has been shown to improve overall sleep.33 Personality

disorders co-present in 10%-15% of adults with ADHD, and children with ADHD are

far more likely to have an antisocial personality disorder as an adult.34

Diagnosis

Numerous

obstacles beset diagnosis of ADHD in adults. The DSM-IV criteria are

geared toward school-age children, yet ADHD persists into adolescence and

adulthood and may not be diagnosed until the adult years.35 Further,

diagnosis of ADHD in adults requires marshalling evidence that the symptoms

began before the age of 7 years old. Self-reports are flawed; aside from

obvious difficulties centered around recalling symptoms that occurred many

years ago,36 adults have been shown to deny symptoms that are

verified by others.37 Difficulty with diagnosis of ADHD in adults is

further compounded by the fact that hyperactive symptoms, which are generally

the easiest symptoms to observe in an interview setting, usually decline with

age. Unlike children, most adults with ADHD have the freedom to avoid overly

structured situations, and a strong base of support at home or at work can make

it difficult to identify substantial impairment in multiple settings. Finally,

the high rate of symptom overlap between comorbid psychiatric disorders in

adults with ADHD impedes diagnosis. Impulsivity, for example, is a defining

symptom of both bipolar disorder and ADHD, while poor concentration is common

in both depression and ADHD.

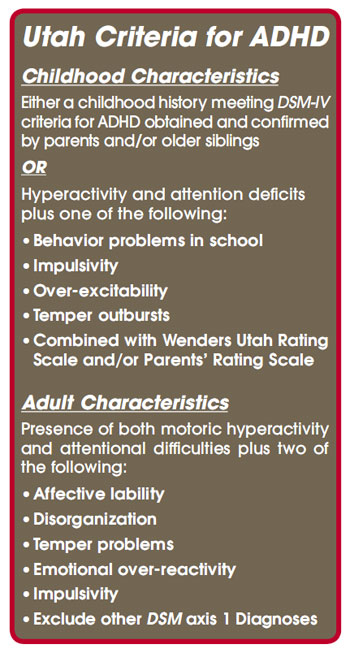

In

order to address the difficulties of retrospectively identifying childhood symptoms,

researchers at the University of Utah School of Medicine Department of Psychiatry

have developed a set of criteria for diagnosing ADHD in adults.38

The Utah Criteria eschew specific cataloguing of childhood symptoms, focusing

instead on recollection of problem areas that may be more easily recalled by

the patient or a parent or former teacher (eg, behavior problems in school).

The Utah Criteria may result in a more inclusionary diagnosis than strictly

following the DSM-IV criteria, and this could, in turn, result in

identifying patients who would benefit from treatment despite not meeting

formal diagnostic criteria.39

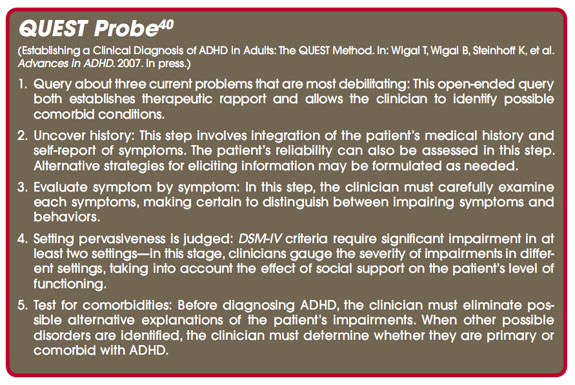

Recently,

investigators at the University of California, Irvine, Child Development Center

have developed a method of more effectively diagnosing ADHD in adults. Called

“QUEST,’ the method is geared toward identifying the problematic behaviors in

adults with age-appropriate probes combined with a logical, careful approach.

- Query about three current problems that are most debilitating:

This open-ended query both establishes therapeutic rapport and allows the

clinician to identify possible comorbid conditions.

- Uncover history: This step involves integration of the patient’s medical history and self-report

of symptoms. The patient’s reliability can also be assessed in this step. Alternative

strategies for eliciting information may be formulated as needed.

- Evaluate symptom by symptom: In this step, the clinician must carefully

examine each symptoms, making certain to distinguish between impairing symptoms

and behaviors.

- Setting pervasiveness is judged: DSM-IV criteria

require significant impairment in at least two settings—in this stage,

clinicians gauge the severity of impairments in different settings, taking into

account the effect of social support on the patient’s level of functioning.

- Test for comorbidities: Before diagnosing ADHD, the

clinician must eliminate possible alternative explanations of the patient’s

impairments. When other possible disorders are identified, the clinician must

determine whether they are primary or comorbid with ADHD.

Management

Management of adult ADHD

should involve both psychosocial and pharmacologic treatment. Counseling and

patient education is recommended,39 and evidence suggests that

cognitive behavioral therapy in conjunction with pharmacotherapy outperforms

pharmacotherapy alone.41

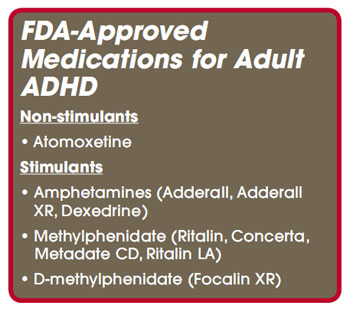

Atomoxetine

was the first medication approved by the FDA for treating adults with ADHD, and

it currently is the only non-stimulant medication with this labeled indication.

Atomoxetine, a selective norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, shows limited

clinical efficacy in adults, but a number of studies indicate it has promise

particularly for some patients.42,43

The

FOCUS (Formal Observation of Concerta versus Strattera) study, published in

2005, indicated that, while both methylphenidate and atomoxetine are effective

treatments for ADHD, methylphenidate is associated with significantly greater

symptom improvement.44 Because atomoxetine is not a Schedule II

medication, practitioners may be more inclined to prescribe it for patients

with a history of substance abuse or tic disorders.45,46

However, atomoxetine use produces a number of side effects including dry mouth, insomnia, nausea, and erectile difficulty.45,46

Blood pressure should also be monitored in patients taking this medication.47

Psychostimulants

are first-line treatments for ADHD due to their established efficacy and

safety. Methylphenidate (MPH) has been shown to be effective in adults48

and is now available in an FDA-approved extended-release formulation.

Amphetamines are similarly effective as MPH, and are often prescribed as a

second-line treatment when MPH is not well-tolerated or does not lead to optimal

efficacy.49 D-methylphenidate functions similarly to MPH, but only

half the dose size is required and it may have an altered side-effect profile.50

Adverse events most commonly observed with stimulant treatment are headache,

abdominal pain, jitteriness, decreased appetite, delayed sleep onset, social

withdrawal, and loss of appetite, and dry mouth has been reported in adults in

particular.51

References

1.

Biederman J, Monuteaux M, Mick E, et al. Young adult outcome of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: a controlled 10

year follow-up study. Psychol Med. 2006;36:167-179.

2.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkle R, et al. the prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the

National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716-723.

3.

Milstein RB, Wilens TE, Biederman J, et al. Presenting ADHD symptoms and subtypes in clinically referred adults with ADHD. J

Atten Disord. 1997;2:159-166.

4.

McGough JJ, Smalley SL, McCracken JT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder:

findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1621-1627.

5.

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, et al. Functional impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD: a controlled

study of 1001 adults in the community. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:524:540.

6.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkley R, et al. The prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the

National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716-723.

7.

Faraone SV, Sergeant J, Gillberg C, et al. The worldwide prevalence of ADHD: is it an American condition? World Psychiatry.

2003;163:716-723.

8.

Borland BL, Heckman HK. Hyperactive boys and their brothers: a 25-year follow-up study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1976;33:669-675.

9.

Morrison JR. Childhood hyperactivity in an adult psychiatric population: social factors. J Clin Psychiatry. 1980;41:40-43.

10.

Wilens TE, Biederman J, Mick E. Does ADHD affect the course of substance abuse? Findings from a sample of adults with and

without ADHD. Am J Addict. 1998;7:156-163.

11.

Tarter RE. Psychosocial history, minimal brain dysfunction and differential drinking patterns of male alcoholics. J

Clin Psychol. 1982;38:867-873.

12.

Murphy K, Barkley RA. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder adults comorbidities and adaptive impairments. Compr

Psychiatry. 1996;37:393-401.

13.

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, et al. Functional impairments in adults with self-reports of diagnosed ADHD: A controlled

study of 1001 adults in the community. J Clin Psychiatry. 2006;67:524-540.

14.

Barkley RA, Fischer M, Fletcher K, et al. Persistence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder into adulthood as a function

of reporting source and definition of disorder. J Abnorm Psychol. 2002;111:279-289.

15.

Weiss M, Murray C. Assessment and management of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder in adults. CMAJ. 2003;168:715-722.

16.

Barkley RA. Major life activity and health outcomes associated with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin

Psychiatry. 2002;63(Suppl 12):10-15.

17.

Shekin WO, Asarnow RF, Hess E, et al. A clinical and demographic profile of a sample of adults with attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder, residual state. Compr Psychiatry. 1990;31:416-425.

18.

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Spencer T, et al. Patterns of psychiatric comoribidty, cognition, and psychosocial funcitioning

in adults with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:1792-1798.

19.

Mcough JJ, Smalley SL, McCracken JT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder:

findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1621-1627.

20.

Kessler RC, Berglund P, Demler O, Jin R, Merikangas KR, Walters EE. Lifetime prevalence and age-of-onset distributions

DSM-IV disorders in the national Comorbidity Survey Replication. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2005;62:593-602.

21.

Wilens TE. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder and the substance use disorders: the nature of the relationship, subtypes

at risk, and treatment issues. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2004;27:283-301.

22.

Rush CR, Higgins ST, Vansickel AR, Stoops WW, Lile JA, Glaser PE. Methylphenidate increases cigarette smoking. Psychopharmacology

(Berl). 2005;181:781-789.

23.

Wilens TE, Faraone SV, Biederman J, Gunawardene S. Does stimulant therapy of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder beget

later substance abuse? A meta-analytic review of the literature. Pediatrics. 2003;11:179-185.

24.

Sobanski E. Pschiatric comorbidity in adults with attention-deficity/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur Arch Psychiatry

Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:26-31.

25.

Kessler RC, Adler L, Barkle R, et al. the prevalence and correlates of adult ADHD in the United States: results from the

National Comorbidity Survey Replication. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:716-723.

26.

Mcough JJ, Smalley SL, McCracken JT, et al. Psychiatric comorbidity in adult attention deficit hyperactivity disorder:

findings from multiplex families. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1621-1627.

27.

Wender PH, Reimherr FW, Wood D, Ward M. A controlled study of methylphenidate in the treatment of attention deficit disorder,

residual type, in adults. Am J Psychiatry. 1985:142:547-552.

28.

Sobanski E. Psychiatric comorbidity in adults with attention-deficity/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Eur Arch Psychiatry

Clin Neurosci. 2006;256:26-31.

29.

Markowitz JS. Drug interactions with stimulant medications. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 1999;14:1-18.

30.

Greenhill LL, Pliszka S, Dulcan MK, et al. Practice parameter for the use of stimulant mediaction in the treatment of children,

adolescents and adults. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2002;41:26S-49S.

31.

Nierenberg AA, Mihahara S, Spencer T, et al. Clinical and diagnostic implications of lifetime comorbidity of attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder in adults with bipolar disorder.Data from the first 1000 STEP-BD participants. Biol Psychiatry. 2005:57;1467-1473.

32.

Brown TE, McMullen WJ. Attention deficit disorders and sleep/arousal disturbance. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2001;931:271-286.

33.

Kooj JJS, Huub AM, Middelkoop AM, Van Gils K, Buitelaar JK. The effect of stimulants on nocturnal activity and sleep quality

in adults with ADHD: an open-label case-control study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:952-955.

34.

Manuzza S, Klein RG, Bessler A, Malloy P, La Padula M. Adult outcome of hyperactive boys. Educational achievement, occupational

rank, and psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:565-567.

35.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

36.

Faraone SV, Biederman J, Doyle A, et al. Neuropsychological Studies of Late Onset and Subthreshhold Diagnoses of Adult

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2006;60:1081-1087.

37.

Ward MF, Wender PH, Reimherr FW. The Wender Utah Rating Scale: an aid in the retrospective diagnosis of childhood attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1993;150:885-890.

38.

Wender PH. Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Adults. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1995.

39.

Ginsberg D, Donnely C, Reimherr F, Young J. Differential diagnosis and treatment of adult ADHD and neighboring disorders. CNS

Spectr. 2006;10(Suppl 11):1-16.

40.

Establishing a Clinical Diagnosis of ADHD in Adults: The QUEST Method. Wigal T, Wigal B, Steinhoff K, et al. Advances

in ADHD. 2007. In press.

41.

Safren SA, Otto MW, Sprich S, Winett CL, Wilens TE, Biederman J. Cognitive-behavioral therapy for ADHD in medication-treated

adults with continued symptoms. Behav Res Ther. 2005;43:831-842.

42.

Adler LA, Spencer TJ, Milton DR, et al. Long-term, open-label study of the safety and efficacy of atomoxetine in adults

with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: an interim analysis. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:294-299.

43.

Michelson D, Adler L, Spencer T, et al. Atomoxetine in adults with ADHD: two randomized, placebo-controlled trials. Biol

Psychiatry. 2003;53:112-120.

44.

Starr HL, Kemner J. Multicenter, randomized, open-label study of OROS methylphenidate versus atomoxetine: treatment outcomes

in African-American children with ADHD. J Natl Med Assoc. 2005;97:11S-16S.

45.

Wilens TE. Impact of ADHD and its treatment on substance abuse in adults. J Clin Psychiatry. 2004;65(Suppl 3);38-45.

46.

Allen AJ, Kurlan RM, Gilbert DL, et al. Atomoxetine treatment in children and adolescents with ADHD and comorbid tic disorders. Neurology.

2005;65:1941-1949.

47.

Nissen SE. ADHD and cardiovascular risk. N Engl J Med. 2006;354:1445-1448.

48.

Spencer T, Biederman J, Wilens T, et al. A large, double-blind, randomized clinical trial of methylphenidate in the treatment

of adults with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:456-463.

49.

Wender EH. Managing stimulant medication for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Pediatr Rev. 2001;22:183-189.

50. Dexmethylphenidate (Focalin) for ADHD. Med Lett. 2002;44:45-46.

51.

Graydanus DE, Sloane MA, Rappley MD. Psychopharmacology of ADHD in adolescents. Adolesc Med. 2002;3:599-624.