Click here to go to the CME post-test

Print Friendly

Special Considerations in Diagnosing and Treating ADHD

Part 1: Preschool-Age Children

Sharon Wigal, PhD

Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of California, Irvine

Timothy Wigal, PhD

Associate Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of California, Irvine

This is the first in a 3-part Psychiatry Weekly CME series on special considerations in diagnosing and treating

ADHD. Parts 2 and 3 in

this CME series will focus on the adolescent and adult populations respectively.

Accreditation Statement

This

activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essentials and Standards of the Accreditation Council

for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and MBL Communications,

Inc. The Mount Sinai School of Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

This

activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essentials and Standards of the Accreditation Council

for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and MBL Communications,

Inc. The Mount Sinai School of Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit Designation

The Mount Sinai School of Medicine designates this educational activity for a maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM.

Physicians should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in the activity.

Faculty Disclosure Policy Statement

It is the policy of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine to ensure objectivity, balance, independence, transparency, and

scientific rigor in all CME-sponsored educational activities. All faculty participating in the planning or implementation

of a sponsored activity are expected to disclose to the audience any relevant financial relationships and to assist in

resolving any conflict of interest that may arise from the relationship. Presenters must also make a meaningful disclosure

to the audience of their discussions of unlabeled or unapproved drugs or devices.

This activity has been peer reviewed and approved by Eric Hollander, MD, Professor of Psychiatry and Chair at Mount Sinai

School of Medicine. Review Date: March 28, 2007.

Statement of Need

An estimated 6%–9% of children are affected by attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The diagnosis of

ADHD involves clinical evaluation of inattentive, impulsive, and hyperactive symptoms. Diagnosis of preschool age children

presents a number of unique difficulties hinging around distinguishing symptoms from natural childhood exuberance and inattention.

Treatment in this patient population has not been well-researched. Amphetamines are the only agents approved by the FDA

for the treatment of ADHD in children between the ages of 3 and 6 years at this time, but off-label methylphenidate is

the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medication for this population. Behavioral interventions have also shown promise.

An important educational need exists to refine the diagnostic and treatment strategies of clinicians in order to more

safely and effectively treat preschool-age children with ADHD. Early, accurate diagnosis is paramount, and clinicians must

remain aware of the newest information on treatment options, both pharmacotherapeutic and behavioral, available to treat

this patient population.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the importance of early and accurate diagnosis of preschool-age patients with ADHD and how comorbidity

may result in misdiagnosis.

- Assess available treatments, both off- and on-label, for safety and efficacy in preschool-age children

with ADHD.

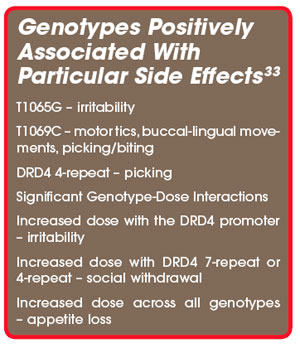

- Explain the latest information on the genetics and etiology of ADHD in preschool-age children and understand

how this affects treatment response and side effect profiles.

Target Audience

This activity will benefit psychiatrists, hospital staff physicians, and office-based “attending” physicians

from the community.

Funding/Support

This activity is supported by an educational grant from Shire.

Faculty Disclosures

Sharon Wigal, PhD, has disclosed that she has received research support from Cephalon, Eli Lilly, McNeil,

New Rivers, NIH, and Shire; has served as an advisor or consultant to Cephalon, McNeil, New Rivers, Novartis, Shire, and

UCB; and has served on the speaker’s bureau for McNeil, Shire, and UCB.

Timothy Wigal, PhD, has disclosed that he has received research support from Cephalon, Eli Lilly, McNeil,

New Rivers, NIH, Novartis, and Shire; has served as a consultant or advisor to McNeil, Novartis, and Shire; and has served

on the speaker’s bureau of McNeil and Shire.

Peer Reviewers

Eric Hollander, MD, reports no affiliation with or financial interest in any organization that may pose

a conflict of interest

Daniel Stewart, MD, PhD, reports no affiliation with or financial interest in any organization that may

pose a conflict of interest.

To Receive Credit for this Activity

Read this poster, reflect on the information presented, and then complete the CME quiz found in the accompanying brochure

or online (www.mssmtv.org/psychweekly). To obtain credit you should score 70% or better. The estimated time to complete this

activity is 1 hour.

Release Date: April 23, 2007

Termination Date: April 23, 2009

Introduction

While the literature on ADHD in

preschool-age children is limited, and the validity of the diagnosis in

children this age is contested, current prevalence estimates for this

population range between two and five percent.1 In addition, there

is substantial evidence linking ADHD symptoms in preschool-age children with

significant concomitant functional impairment and behavioral problems in later

childhood.2-8 Treatments utilized by clinicians for this population

include psychosocial treatment and the prescription of stimulants. While

methylphenidate (MPH) is the most widely used stimulant medication for treating

preschool children, MPH is not FDA-approved for use in children under the age

of 6, and few studies have examined stimulants in this population.9-10

In addition, a relatively recent study reported a 49% increase in their prescription

to children under the age of 5.9 The tentatively favorable findings

of one large NIMH-funded study on the safety and efficacy of MPH—the Preschool

ADHD Treatment Study (PATS)—were recently published in the Journal of the

American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry (2006), but the

authors noted that follow-up research was imperative.

The

lack of literature on ADHD in preschool-age children in combination with the

confusion surrounding reliable diagnosis, apparent prevalence of the disorder,

and the associated significant impairments indicate a clear and pressing need

for increased study of ADHD and ADHD-like behaviors in young children and

merits a revisiting of current best understanding and practice.

Diagnosis

A diagnosis of ADHD by DSM-IV

criteria may be classified in three ways: predominately inattentive,

predominately hyperactive-impulsive, and combined-type (both inattentive and

hyperactive-impulsive).

The

application of these criteria to young children poses problems particular to

the age group; not only is it difficult to identify inattentiveness

inconsistent with age level in preschoolers—who are, in general, far more

inattentive than older children—but it is equally difficult to identify hyperactivity-impulsivity

inconsistent with age level in this population. In essence, a certain degree of

inattentiveness and hyperactivity are the developmental standard for young

children. The key is in assessing whether the symptoms are maladaptive.

However, identifying maladaptive inattentiveness in preschool-age children is

further complicated by the fact that young children are seldom in situations

where they are asked to sustain attention. Indeed, a lack of sustained

attention is seldom maladaptive for this population—impairment is most likely

to be associated with hyperactivity.

Because ADHD is more likely to

negatively affect functioning at school, teachers are often the first to notice

a problem. The shift in preschool away from, essentially, group daycare toward

a more structured learning environment has likely contributed to the

identification of maladaptive hyperactivity, due to its disruptive nature in a

classroom setting, as well as, to a lesser extent, maladaptive inattentiveness

(again, if one is not asking a child to attend, inattentiveness will tend to go

unnoticed). Conversely, evidence suggests that parents with a child who does

meet criteria for ADHD are significantly more likely to consider hyperactivity

and inattentiveness as developmentally standard in comparison to parents whose

children do not meet criteria for ADHD.11

In

assessing a child who may have ADHD, a clinician needs to first rule out

alternative explanations for the ADHD-like symptoms. These can include, but are

by no means limited to significant life change (eg, parents’ divorce), learning

disability, a mood or anxiety disorder, and/or seizures and other medical

disorders that affect brain functioning. (NIMH ADHD site) A

thorough history, including school and medical records, and an examination of the home and classroom environment should be

the foundation of an ADHD diagnosis. The child’s teachers can be an invaluable

source of information—although generally not trained mental health

professionals, their access to comparator children (as generally opposed to a

parent’s access to same) lends significant credence to their (ie, the

teachers’) subjective measures of a child’s behavior.

Due

to the natural hyperactivity and inattentiveness of young children, a clinician

must be confident that these symptoms cause impairment to make an ADHD

diagnosis in this population.

Etiology

Over

the years, many theories regarding the cause of ADHD have been advanced, some

with more credence than others. Two views that have not withstood scientific scrutiny

are the theories that poor parenting or exposure to certain food additives

cause the disorder. Little evidence for either has been found, although diet

restriction may have a positive effect on ADHD symptoms in some young children

with food allergies.12 A positive correlation has been found between

alcohol and cigarette use during pregnancy. (NIMH

ADHD site)

There

is strong evidence for a genetic element to ADHD from both family and twin

studies.13-14 ADHD has been found to be five times more common in

the close relatives of those with ADHD than in the general population. Research

has identified genes involved in dopamine regulation, but ADHD does not appear

to be a “one-gene” disorder. Variants in the dopamine D4 receptor gene,

the dopamine DRD5 gene, and a dopamine transporter gene have all been linked

with susceptibility to ADHD.15-17

A number of

other genes have been associated with the developmental course of the disorder,

including the DRD4 7-repeat risk allele (influences persistence and antisocial

behavior), a functional variant in the gene encoding COMT (associated with

antisocial behavior in ADHD), and a variant in MAOA (associated with antisocial

behavior in ADHD).18-21

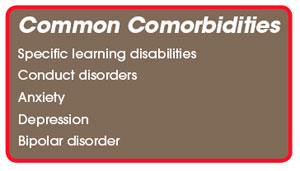

Common Comorbidities

Comorbidities

are highly prevalent in ADHD (up to 50% of children with ADHD have at least one

comorbid disorder).22 Comorbidities are more commonly identified in

older children and adults with ADHD than in preschool children; this may be

due, in part, to later emergence of certain psychiatric disorders, but is

likely also partly accounted for by the difficulty of diagnosing psychiatric

disorders in young children.

20%–30%

of children with ADHD have a specific learning disability.23 Conduct

disorders, particularly oppositional defiant disorder, are also common

comorbidities (they’re present in up to 50% of children with ADHD, though

oppositional defiant disorder predominately presents in boys). Anxiety and

depression also co-present with ADHD. Some suspect bipolar disorder is also a

common comorbidity, but there are no agreed-upon prevalence  rates. In part,

this is because bipolar disorder is difficult to diagnose in children. However,

the picture is further complicated in that bipolar disorder appears to present

in children as a chronic mood dysregulation (without the cycling so important

to an adult diagnosis), making the symptoms very similar to those of ADHD.

Elated mood and grandiosity, however, are particular to children with bipolar

disorder, and can form the basis for a distinction.24

rates. In part,

this is because bipolar disorder is difficult to diagnose in children. However,

the picture is further complicated in that bipolar disorder appears to present

in children as a chronic mood dysregulation (without the cycling so important

to an adult diagnosis), making the symptoms very similar to those of ADHD.

Elated mood and grandiosity, however, are particular to children with bipolar

disorder, and can form the basis for a distinction.24

In very young

children, ADHD also shares a similar symptom cluster with autism. The similarity

of ADHD symptoms and the symptoms of other psychiatric disorders in very young

children, coupled with the difficulty of diagnosing preschool-age children, has

likely led to instances of both under and over-diagnosis of ADHD in this

patient population.

Treatment

Amphetamines (ie,

dextroamphetamine and mixed amphetamine salts) are the only agents approved by

the FDA for the treatment of ADHD in children between the ages of 3 and 6 years

at this time. Although MPH is not approved for children under 6 years of age,

it is the most commonly prescribed psychotropic medication for ADHD patients in

this population. In response to increased off-label prescription of stimulants

for preschool-age children, the National Institute of Health Consensus

Development Conference on the Diagnosis and Treatment of ADHD (1998) found a

need for further study on the safety and efficacy of stimulant medications in

young children with ADHD. Specifically, researchers stressed the need for a

better understanding of age-related effects on drug absorption and metabolism,

dose-response characteristics, and side effects of using stimulants in

preschool-age children.

The Preschool ADHD Treatment

Study (PATS) (2006) was designed to answer this call for further study. A small

handful of previous studies had produced conflicting results on MPH in preschool-age

children, with two identifying no difference in response to placebo and MPH25-26

and one indicating increased adverse events in younger children taking MPH as

opposed to older children on MPH.27 These studies were subject to

methodological differences, particularly in relation to inclusion/exclusion

criteria. The PATS was a large, multi-site trial with rigorous criteria for

inclusion and exclusion. Prior to admittance to the study, prospective subjects

underwent extensive assessment, and all cases required a consensus agreement of

acceptability from a cross-site panel of clinicians prior to admittance.

The study found significant

evidence for the efficacy of MPH in preschool-age children when administered

2.5, 5, and 7.5 mg TID. No significant improvement was found for children receiving

1.25 mg TID. The optimal dose for the preschoolers was 14.2±8.1 mg/day. Significantly higher doses were

required for maintenance of response during the 10-month treatment period.

Despite the

reduction of ADHD symptoms in the PATS subjects taking MPH, effect sizes were

significantly lower than those recorded in prior studies of older children. The

authors suggest this could be due to age-specific differences in treatment

response, differences in study design between PATS and prior large studies of

MPH response in older children, or a combination thereof.

Safety and Tolerability of MPH

The

5 most common adverse events (AEs) in the PATS were decreased appetite,

difficulty sleeping, repetitive behaviors, emotional outbursts, and

irritability. Parent-rated AEs for MPH that were significantly greater than

those for placebo were appetite decrease, trouble sleeping, and weight loss. No

significant differences in AEs were recorded between different dose sizes of

MPH. No cardiovascular AEs were observed.

The

PATS uncovered notable differences between AEs in preschool-age children on MPH

and older children on MPH. Discontinuation rates were higher in PATS (11%) than

in the large, MTA Cooperative Study Group (1999) examination of MPH in

school-age children (<1%). Furthermore, preschool-age children demonstrated

a different profile of moderate to severe AEs than that found in school-age

children. The latter were subject to decreased appetite, delay of sleep onset,

headaches, and stomach aches.

The

PATS uncovered notable differences between AEs in preschool-age children on MPH

and older children on MPH. Discontinuation rates were higher in PATS (11%) than

in the large, MTA Cooperative Study Group (1999) examination of MPH in

school-age children (<1%). Furthermore, preschool-age children demonstrated

a different profile of moderate to severe AEs than that found in school-age

children. The latter were subject to decreased appetite, delay of sleep onset,

headaches, and stomach aches.

The MPH-related AEs in

preschool-age children with ADHD, although more aversive than in their older

counterparts, appeared, on the whole, manageable. The authors of the PATS

noted, however, that a much larger study (N>1,500) is required to meet

regulatory guidelines for establishing side-effect profile.

Evidence

also suggests28 that persistent treatment with a stimulant can

significantly lower the growth rate in young children; however, this

possibility needs to be balanced against the likely benefit of treatment on a

case-by-case basis.

The

related finding that preschool-age children require higher concentrations of

MPH in their blood to achieve the same behavioral effects as those seen in

school-age children is somewhat surprising.29 Medication absorption

and clearance is likely affected not just by weight, but by differences in

physiology (as relating to either structure or particular enzymes) between

younger and older children. Further analysis of these relationships is critical

to properly inform dosing. It seems evident that size and weight are not the

only salient factors.30

Psychosocial Treatment

The

MTA study of school-age children with ADHD found that, while medication

treatment as delivered in the study was highly effective, behavioral treatment

was equally effective to the medication treatment delivered in the community,

and combination therapy was most effective of all. However, these differences

disappeared at follow-up. The PATS did not examine behavioral treatments in

preschool-age children, but rather, parent training prior to initiation of

medication treatment. Prior work demonstrated that parent training produced

clinically significant symptom improvement in preschool-age children with ADHD

(as well as increasing ratings of maternal well-being).31

The

success of psychosocial treatment in older children, preliminary evidence for

the efficacy of behavioral treatments in preschool-age children, the

side-effect profile of stimulants in young children, and issues surrounding

parent resistance to medicating their children all warrant further study of

psychosocial intervention and combination therapy in young children with ADHD.

While some parents turn to alternative treatments—eg, natural supplements—there

is currently no evidence supporting their efficacy.

In summary, both medication and

behavioral treatments appear to alleviate the symptoms of ADHD. Most evidence

suggests that discontinuation of treatment leads to the reemergence of the

condition. ADHD is a chronic problem. At the present time, efforts are

continuing towards understanding the genetic underpinnings of ADHD. Early

identification and treatment of symptoms of ADHD preschool-age children may

contribute to more positive outcomes.

To take the free, online CME post-test, go to www.mssmtv.org/psychweekly

References

1. Lavigne JV, Gibbons RD, Christoffel KK, et al. Prevalence rates and correlates of psychiatric

disorders among preschool children. J

Am Acad Child Adolesc. 1996;32:204-214.

2. Campbell SB. Parent-referred problem three-year-olds: developmental changes in symptoms. J Child Psychol

Psychiatry.

1987;28:835-845.

3. DuPaul GJ, McGoey KE, Eckert TL, VanBrakle J. Preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder: impairments in behavioral, social, and school functioning. J Am Acad Child Adolesc.2001;40:508-515.

4. Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Stein MA, et al. Validity of DSM-IV attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder for younger children. J

Am Acad Child Adolesc. 1998;37:695-702.

5. LaHoste GJ, Swanson JM, Wigal SB, et al. Dopamine D4 receptor gene polymorphism is associated

with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Mol Psych. 1996;1:121-124.

6. Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, et al. Three-year predictive validity of DSM-IV attention

deficit hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4Y6 years of age. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:2014-2020.

7. Pierce EW, Ewing LJ, Campbell SB. Diagnostic status and symptomatic behavior of hard-to-manage

preschool children in middle childhood and early adolescence. J Clin Child Psychol. 1999;28:44-57.

8. Wilens TE, Biederman J, Brown S, Monuteaux M, Prince J, Spencer TJ. Patterns of psychopathology

and dysfunction in clinically referred preschoolers. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 2002;23:S31-S36.

9. Medco Health Solutions. 2004 Drug Trend Report. www.medcohealth.com. Accessed May 17,

2004.

10. Zito JM, Safer DJ, dosReis S, Gardner JF, Boles M, Lynch F. Trends in the prescribing of psychotropic medications

to preschoolers. JAMA.

2000;283:1025-1030.

11. Manidiaki K, Sonuga-Barke E, Kakouros E, Karaba R. Parental beliefs about the nature of ADHD behaviours and their

relationship to referral intentions in preschool children. Child Health Care Dev. 2007;33:188.

12. Consensus Development Panel. Defined Diets and Childhood Hyperactivity. National Institutes of Health Consensus Development

Conference Summary, Volume 4, Number 3, 1982.

13. Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, Knee D, Tsuang MF. Family-genetic and psychosocial risk factors in DSM-III attention

deficit disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1990;29:526-533.

14. Faraone SV, Biederman J. Neurobiology of attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder. Bio Psych. 1998;44;951-958.

15. Faraone SV, Perlis RH, Doyle AE, et al. Molecular genetics of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Bio Psych,.

2005;57:1313-1323.

16. Kennedy JL. Dopamine D4 receptor gene polymorphism is associated with attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder. Mol

Psych. 2004;1:121-124.

17. Lowe N, Kirley A, Hawi Z, et al. Joint analysis of the DRD5 marker concludes association with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder confined to the predominantly inattentive and combined subtypes. Am J Hum

Genet. 2004;74:348-356.

18. El-Faddagh, M., Laucht, M., Maras, A., et al. Association of dopamine D4 receptor (DRD4) gene with attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder (ADHD) in a high-risk community sample: a longitudinal study from birth to 11 years of age. J Neur Trans.

2004;111: 883-889.

19. Swanson JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, et al. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: success rates based

on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. 2001:40;168-179.

20. Thapar A, Langley K, Fowler T, et al. Catechol o-methyltransferase gene variant and birth weight predict early-onset

antisocial behavior in children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Archives of General Psychiatry.

2005;62:1275-1278.

21. Thapar A, Langley K, O’Donovan M, et al. Refining the attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder phenotype for molecular genetic studies. Mol Psych. 2006;11:714 –720.

22. MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment strategies for attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder. Arch Journ Psych. 1999;56:1073-1086.

23. Wender PH. ADHD: Attention-Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adults. Oxford University Press.

2002;p. 9.

24. Geller B, Williams M, Zimerman B, Frazier J, Beringer L, Warner KL. Prepubertal and early adolescent bipolarity differentiate

from ADHD by manic symptoms, grandiose delusions, ultra-rapid or ultradian cycling. J Affect Disord. 1998;51:81-91.

25. Barkley RA, The effects of methylphenidate on the interactions of preschool ADHD children with their mothers. J

Am Acad Child Adolesc. 1998;27:336-341.

26. Cohen NJ , Evaluation of the relative effectiveness of methylphenidate and cognitive behavior modification in the

treatment of kindergarten-aged hyperactive children. J Abnormal Child Psychol. 1981;9:43-54.

27. Handen BL, Feldman HM, Lurier A, Murray PJ. Efficacy of methylphenidate among preschool children with developmental

disabilities and ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. 1999;38:805-812.

28. Swanson J, Greenhill L, Wigal T, et al. Stimulant-related reductions of growth rates in the PATS. J Am Acad Child

Adolesc.

2006;45:1304-1313.

29. Wigal S, Gupta S, Greenhill L, et al. Pharmacokinetics of Methylphenidate in Preschoolers With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder. J Child Adolesc Psychopharm. In press.

30. Greenhill L, Kollins S, Abikoff H, et al. Rationale, Design, and Methods of the Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS). J

Am Acad Child Adolesc. 2006;45:11.

31. Sonuga-Barke EJ, Daley D, Thompson M, Laver-Bradbury C, Weeks A. Parent-based therapies for preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity

disorder: a randomized, controlled trial with a community sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc. 2001;40:402-408.

32. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition. Washington, DC; American Psychiatric

Association:1994.

33. McGough JJ. Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder pharmacogenomics. Bio Psych. 2005;57:1367-1373.

34. Kollins S, Greenhill L, Swanson J, et al. Rationale, design, and methods of the Preschool ADHD Treatment Study (PATS). The

J Am Acad Child Adolesc. 2006;45:1275-1283.

To take the free, online CME post-test, go to www.mssmtv.org/psychweekly