Click here to go to the CME post-test

Print Friendly

Special Considerations in Diagnosing and Treating ADHD

Part 2: Children and Adolescents

Sharon Wigal, PhD

Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University of California, Irvine

Timothy Wigal, PhD

Associate Clinical Professor of Pediatrics, University

of California, Irvine

This is the second in a 3-part Psychiatry Weekly CME series on special considerations in diagnosing and treating ADHD. Part

1 focused on the preschool-age population, and part

3 will focus on the adult population.

Accreditation

Statement

This

activity has been planned and implemented in accordance with the Essentials and Standards of the Accreditation Council

for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) through the joint sponsorship of the Mount

Sinai School of Medicine and MBL Communications, Inc. The Mount Sinai School of

Medicine is accredited by the ACCME to provide continuing medical education for physicians.

Credit

Designation

The

Mount Sinai School of Medicine designates this educational activity for a

maximum of 1 AMA PRA Category 1 Credit(s)TM. Physicians

should only claim credit commensurate with the extent of their participation in

the activity.

Faculty

Disclosure Policy Statement

It is the policy of the Mount Sinai School of Medicine to

ensure objectivity, balance, independence, transparency, and scientific rigor

in all CME-sponsored educational activities. All faculty participating in the

planning or implementation of a sponsored activity are expected to disclose to

the audience any relevant financial relationships and to assist in resolving

any conflict of interest that may arise from the relationship. Presenters must

also make a meaningful disclosure to the audience of their discussions of unlabeled

or unapproved drugs or devices.

This

activity has been peer reviewed and approved by Eric Hollander, MD, Professor

of Psychiatry and Chair at Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Review Date: May 9, 2007

Statement of Need

ADHD is the most common

childhood psychiatric disorder, and children with the disorder are subject to

long-term social and academic impairment. The cost to society has been estimated

at over 30 billion dollars per year. Diagnosis of ADHD in school-age children

and adolescents requires the presence of symptoms in two or more different

environments and generally involves symptom assessments from both parents and

teachers. The diagnosis is further complicated by the high frequency of

comorbid psychiatric disorders in this patient population. ADHD is strongly

genetic, but no specific genes have yet been implicated in the disorder.

Medication,

psychosocial therapy, and combined treatment have all been shown effective for

reducing symptoms, but ADHD does not fully resolve, either on its own or with

treatment. School-age children and adolescents with ADHD need effective,

long-term symptom management. Non-amphetamine medications are being explored,

and some have demonstrated success, but amphetamines are still the most

effective medication in reducing ADHD symptoms. Treatment noncompliance is

high, particularly in older children and adolescents—new methods of drug

delivery are being explored to address this issue.

An important educational need exists to

improve identification of ADHD by both psychiatrists and general

practitioners. Clinicians must also stay abreast of the evidence on efficacy,

adverse events, and compliance for pharmacotherapeutic, behavioral, and combined

treatments.

Learning Objectives

- Describe the impact of ADHD on children and adolescents and the difficulties

inherent in diagnosing this patient population.

- Assess the evidence on treatment efficacy, safety, and compliance in

children and adolescents with ADHD.

- Explain the current information on the etiology and likely course of ADHD in

children and adolescents with ADHD, and understand how this impacts diagnosis

and treatment.

Target Audience

This activity will

benefit psychiatrists, hospital staff physicians, and office-based “attending”

physicians from the community.

Funding/Support

This activity is supported by an educational

grant from Shire.

Faculty Disclosures

Sharon

Wigal, PhD, has disclosed that she has received research support from

Cephalon, Eli Lilly, McNeil, New Rivers, NIH, and Shire; has served as an

advisor or consultant to Cephalon, McNeil, New Rivers, Novartis, Shire, and

UCB; and has served on the speaker’s bureau for McNeil, Shire, and UCB.

Timothy Wigal, PhD, has disclosed that

he has received research support from Cephalon, Eli Lilly, McNeil, New Rivers,

NIH, Novartis, and Shire; has served as a consultant or advisor to McNeil,

Novartis, and Shire; and has served on the speaker’s bureau of McNeil and Shire.

Peer Reviewers

Eric Hollander, MD, reports no

affiliation with or financial interest in any organization that may pose a

conflict of interest

Daniel Stewart, MD, PhD, reports no

affiliation with or financial interest in any organization that may pose a conflict

of interest.

To Receive Credit for this Activity

Read

this poster, reflect on the information presented, and then complete the CME

quiz found in the accompanying brochure or online (www.mssmtv.org/psychweekly).

To obtain credit you should score 70% or better. The estimated time to complete

this activity is 1 hour.

Release Date: June 6, 2007

Termination Date: June 6, 2009

Introduction

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) is the most common childhood psychiatric disorder.1 Children

who suffer from the disorder are subject to significant short- and long-term academic deficiencies,2 social

impairment,3 and the overall annual societal cost of the disorder has been estimated at 36-52.4 billion dollars

($12,005-$17,548 per child per year, 5% prevalence).4 Contrary to previous belief, the disorder does not resolve

with puberty for the majority of children.5-6 Diagnosis is particularly difficult due in large part to the pronounced

comorbidity of psychiatric disorders in this patient population,7 which can result in both over- and under-diagnosis.8-10 Difficulties

are compounded by the large role of primary care practitioners—who may not be as familiar with the disorder as psychiatrists—in

both diagnosis and treatment.11 Clearly, ADHD presents a critical challenge to public health in America. Identifying

and aggressively treating ADHD in children and adolescents is essential to effective long-term management of the disorder.

Prevalence

Prevalence

estimates of ADHD in school-aged children (4-17 years) are widely disparate.

One extensive review found estimates ranging from 2%-18% of American children

in community samples.12 The National Institute of Mental Health

(NIMH) estimates the prevalence of ADHD in children at 3%-5%13.

According to a Center for Disease Control analysis of the 2003 National Survey

of Children’s Health (which surveyed parents or guardians of over 100,000 children)

approximately 4.4 million American children and adolescents (7.8% of those aged

4-17) had a history of ADHD diagnosis. In addition, approximately 2.4 million

children (4.3% of those aged 4-17) were found to both have a diagnosis of ADHD

and received medication to treat ADHD.14 Males were 2.5 times more

likely to have been diagnosed than females, and the highest prevalence was

among 16-year-old males (14.9%) and among 11-year-old females (6.1%).

Prevalence of diagnosis was significantly higher for children and adolescents

with insurance and primarily from English-speaking families.

Impact

ADHD in children and adolescents is significantly

associated with disability.

This patient population is prone to below average

academic performance, increased risk of substance abuse, emotional problems,

difficulty with peer relationships, and legal troubles.2,15-17

Teenagers with ADHD who are of driving age are at increased risks for

accidents.18 Parents who have adolescents with ADHD are also

severely impacted; they are subject to chronic stress, and this can have a

negative effect on both the parents and other family members.19

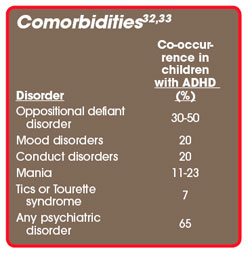

Comorbidities

Children with ADHD are at significantly increased risk

for other psychiatric disorders, including mood, anxiety, and conduct disorders,

and in adolescents, substance abuse disorders.20 Children with ADHD

are also extremely prone to learning disabilities, with estimates of prevalence

ranging from 10% to 92%.21 Comorbid disorders can both worsen the

course of ADHD and impact treatment. For example, anxiety in this patient

population is associated with increased psychiatric treatment and impaired

psychosocial functioning.22

Oppositional Defiant Disorder

and Conduct Disorder

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) and Conduct Disorder

(CD) co-present with ADHD in 30% to 50% of children23 and are of

particular note in that they significantly impact the course of ADHD in

children and are linked to other comorbidities in this patient population. ODD

entails pronounced hostile and defiant behavior, while CD is considered more

severe, and involves habitual rule breaking defined by aggression, destruction,

and lying. CD nearly always follows ODD, however, it has recently been found

that ODD is a poor predictor of later CD onset. Further, ODD + CD is a strong

predictor of substance abuse, while ODD alone is not. There is evidence that,

despite its correlation with more serious clinical course of ADHD, CD does not

significantly alter treatment course in children with ADHD.24-26

Mood Disorders

Lifetime rates of comorbid depression in children with

ADHD range from 29-45%, and comorbid depression predicts impaired psychosocial

and interpersonal functioning, as well as higher hospitalization rates. Mania

is present in 11-23% of children with ADHD and correlates to impaired psychosocial

functioning, psychiatric hospitalization, and additional psychopathology.27

There have also been indications that comorbid bipolar disorder is correlated

with an increased risk of completed suicide attempts.28 Mania and

depression can both complicate an ADHD diagnosis, due to shared developmental

features, but adolescent mania can be more differentiable from ADHD, as the

symptoms of the latter are likely to have preceded the symptoms of the former

by a number of years. There is evidence that mood disorders and ADHD share similar

genetic risk factors.29

Comoribidity and Treatment

Response

The

response to medication treatment is variable, and many children are not

excellent responders30 despite careful titration and management.

Treatment may be more successful depending on the presence of co-morbid

conditions. In general, it has been suggested that a less favorable response to

stimulant treatment for patients with ADHD is correlated with an increase in

the number of co-morbid disorders. For example,

the Multimodal Treatment Study of Children with ADHD (MTA) study, a large,

randomized controlled clinical trial in children with ADHD, noted that

treatment outcome was moderated by both anxiety and depressive symptoms.31

This study is of note because it is free of a referral bias sometimes associated with other studies.

Diagnosis

The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental

Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) criteria for ADHD were originally

based on presentation in school-aged children, so diagnosing school-age

children with ADHD is more straightforward than diagnosing their younger and

older counterparts. The criteria require either 6 or more symptoms of

inattention or 6 or more symptoms of hyperactivity-impulsivity, persisting for

at least six months, inconsistent with developmental level, and producing

significant impairment. There must also be evidence that some symptoms causing

impairment were present before the age of 7, impairment must be present in at

least two settings, and symptoms cannot be better accounted for by another

mental disorder.34 ADHD occurs as one of three subtypes—combined,

inattentive, or hyperactive-impulsive—depending on the relative representation

of the symptom domains.

Generally, the two settings analyzed for presentation of

symptoms are home and school.

Parents

or guardians are predominately responsible for providing information on a young

child’s symptoms at home, but they can either over- or under-represent the

frequency and severity of symptoms. Due to the high heritability of ADHD, it is

very likely that a parent of a child with ADHD will also have symptoms of the

disorder, which can interfere with the parent’s role in the diagnosis. Parents’

perceptions can also be impaired by the lack of a good comparator group. Unlike

a child’s teacher, parents may not have witnessed enough behavior from other

children to accurately compare their own child’s behavior and attention

relative to age-matched peers. There is some evidence that over-reliance on

parental reports of symptoms leads to overdiagnosis, while clinician assessment

of symptoms in their office and self-report from young children result in

underdiagnosis.38

One study39 found a 74% concordance between

parent and teacher assessment of symptoms in younger children with ADHD, and

this concordance rate only falls as children grow into adolescence. While

children in elementary school primarily will spend the entire school day with

one teacher, children in secondary education will have up to 7 separate

teachers a day. Not surprisingly, inter-rater reliability tends to be low among

secondary school teachers when assessing their students.40 Older

children and adolescents are also likely to spend a great deal less time at

home, making it more difficult for the parents to assess their symptoms. There

is also evidence that adolescents are as unlikely to accurately report their

own symptoms as are younger children.41

Collecting evidence of ADHD symptoms present before the

age of 7 in adolescents also presents difficulties as parent, teacher, and

self-report are all likely have difficulties with retrospective recall. A

review of school reports should always be included in all ADHD diagnosis in

children and adolescents, and have particular value as an aid in recall of past

problems.31 Diagnosing ADHD for all age groups is complicated by the

high prevalence of comorbid psychiatric disorders in this population. Children

and adolescents with opposition defiant disorder, bipolar disorder,42

and a variety of anxiety disorders can present quite similarly to ADHD.10

Therefore, a careful differential diagnosis is a necessary and crucial part of

the diagnostic process.

Clinicians diagnosing patients who may have ADHD should

make liberal use of rating scales, which aid not only in identifying symptoms of

ADHD, but, equally important, other psychiatric disorders that might confound

diagnosis. Scales can be roughly broken down into “narrow”—those that focus

specifically on ADHD, and “broad”—those that measure a broader range of

behaviors. Patient self-report scales can augment parent and teacher report

scales, but the clinician must remember that adolescents are extremely likely

to under-represent their symptoms.

There is some debate over the relative prevalence of

ADHD in boys and girls. Until recently, 6 boys were diagnosed for every girl

who was diagnosed with ADHD. Now, the ratio is closer to 3:1. Some suggest that

ADHD may still be underdiagnosed in girls, perhaps due to parent and teacher

preconceptions about gender disparity in ADHD.49 Studies on gender

differences in presentation of ADHD are few and conflicting. Some have found no

significant difference in symptomatology, comorbidity, and neuropsychological

function,50,51 while others suggest that girls with ADHD demonstrate

lower levels of activity and aggression.52,53

Treatment

According to the results of the collaborative, multisite

NIMH-funded, Multimodal Treatment Study of Children With Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder (MTA)—with 579 probands the largest randomized clinical trial of

treatment for ADHD ever attempted—behavioral treatment is effective in children

with ADHD, but both medication treatment and combined behavioral and medication

treatment demonstrate even greater efficacy.54 Of note, treatment

regimens in the MTA study—although constrained to one of four treatment arms:

medication, behavioral, combined treatment, or community-treatment/assessment

and referral, did allow for some individual flexibility in terms of the

intensity of the treatment that was administered. In other words, each

treatment arm was developed as a “management strategy,” allowing for a certain

degree of flexibility in responding to the individual needs of the patients who

may have needed a different dose schedule or “extra” counseling.

Recently,

the field of ADHD treatment has experienced some excitement regarding atomoxetine, a norepinephrine re-uptake inhibitor

and the first FDA-approved non-stimulant medication for ADHD. Atomoxetine does not

carry the same potential for abuse as amphetamines do, and is less likely to

lead to some of the same types of side effects (e.g., insomnia) that can

sometimes prevent effective treatment. However, the precise mechanism of action of

atomoxetine in ADHD has remained elusive and stimulant treatment appears to be significantly more effective in

reducing symptom severity. In fact, the overall side effect profile is comparable between the two drugs.55

A number of alternative treatments for ADHD have also

been explored. According to one extensive review, enzyme-potentiated

desensitization, relaxation/EMG biofeedback, and deleading (a process of

supposedly removing lead from the body) have demonstrated some efficacy in

controlled trials; iron supplementation, magnesium supplementation, Chinese

herbals, EEG biofeedback, massage, meditation, mirror feedback,

channel-specific perceptual training, and vestibular stimulation have shown

some promise in prospective pilot studies. Oligoantigenic (few-foods) diets

appear somewhat effective for children, but do not appear to work for adults.

There are also a number of other alternative treatments with some promise, but

evidence of improved outcome is still very sparse.56

Treatment compliance is a particular concern in treating

ADHD, but recent advances in drug delivery show some promise in reducing

noncompliance in this patient population. Once-a-day amphetamine treatments

have been available for ADHD patients since 2000, and recently, researchers

have been exploring other alternative methods of delivery for methylphenidate.

Of particular note are the osmotic-release delivery system and the transdermal

delivery system. Osmotic release provides consistent drug delivery throughout

the day. The transdermal delivery system or patch has the advantage of ease of

administration while maintaining efficacy for patients who have difficultly

swallowing or tolerating oral treatments.57

To take the free, online CME post-test, go to www.mssmtv.org/psychweekly

References

1.

Olfson M. Diagnosing mental disorders in office-based pediatric practice. J Dev

Behav Pediatr. 1992;13:363-365.

2.

Frazier T, Youngstrom E, Glutting J, Watkins M. ADHD and Achievement:

Meta-Analysis of the Child, Adolescent, and Adult Literature and a Concomitant

Study With College Students. Journal of Learning Disabilities. 2007;40:49-65.

3.

Bagwell C, Molina B, Pelham W, Hoza B. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder

and problems in peer relations: predictions from childhood to adolescence. J Am

Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:1285-1292.

4.

Pelham W, Foster M, Robb J. The Economic Impact of Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity

Disorder in Children and Adolescents. Ambulatory Pediatrics. 2007;7:121-131.

5.

Biederman J, Farone S, Milberger S, et al. A prospective 4-year follow-up study

of attention-deficit/hyperactivity and related disorders. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

1996;53:437-446.

6.

Ingram S, Hechtman L, Morgenstern G. Outcome issues in ADHD: adolescent and

adult long-term outcome. Ment Retard Dev Disabil Res Rev. 1999;5:243-250.

7.

Biederman J, Newcorn JH, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention-deficit

hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety and other disorders.

Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:251-256.

8.

Abikoff H, Courtney M, Pelham WE, Koplewicz HS. Teachers’ ratings of disruptive

behaviors: the influence of halo effects. J Abnorm Child Psychol. 1993;21:519-533.

9.

Schachar R, Sandber S, Rutter M. Agreement between teachers’ ratings and

observations of hyperactivity, inattentiveness and defiance. J Abnorm Child

Psychol. 1986;14:331-345.

10.

Pliszka SR. Effect of anxiety on cognition, behavior and stimulant response in

ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1989;28:882-887.

11.

Rappley MD, Gardiner JC, Jetton JR, Houang RT. The use of methylphenidate in

Michigan. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149:675-679.

12.

Rowland AS, Lesesne CA, Abramowitz AJ. The epidemiology of

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): a public health view. Mental

Retardation Developmental Disability Research Review 2002;8:162--70.

13.

NIMH. Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder. 2006.

http://www.nimh.nih.gov/publicat/adhd.cfm#intro. Accessed April 19, 2007.

14.

Mental Health in the United States: Prevalence of Diagnosis and Medication

Treatment for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder --- United States, 2003.

MMWR. September 2, 2005 / 54(34);842-847.

15.

Wilens T. Alcohol and other drug use and attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder. Alcohol Health Res World. 1998;22:127-130.

16.

Gittelman R, Mannuzza S, Shenker R, Bonagura N. Hyperactive boys almost group

up: I. Psychiatric status. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1985;42:937-947.

17.

Hechtman L, Weiss G. Controlled prospective fifteen year follow-up of

hyperactives as adults: non-medical drug and alcohol use and anti-social

behaviour. Can J Psychiatry. 1986;31:557-567.

18.

Barkley R. Driving Impairments in teens and adults with

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Psychiatr Clin North Am.

2004;27:233-260.

19.

Johnston C, Mash E. Families of children with attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder: review and recommendations for future research. Clin Child Family

Psychol. 2001;4:183-207.

20.

Biederman J, Wilens T, Mick E, et al. Does attention-deficit hyperactivity

disorder impact the developmental course of drug and alcohol abuse and dependence?

Boil Psychiatry. 1998;36:37-43.

21.

Silver LB. The relationship between learning disabilities, hperactivty,

distractibility, and behavioral problems. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry.

1981;20:385-397.

22.

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Mick E, et al. Attention deficit hyperactivity

disorder and juvenile mania: an overlooked comorbidity? J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 1996;35:997-1008.

23.

Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of attention deficit

hyperactivity disorder with conduct, depressive, anxiety, and other disorders.

Am J Psychiatry. 1991;148:564-577.

24.

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Milberger S, et al. Is childhood oppositional defiant

disorder a precursor to adolescent conduct disorder? Findings from a four-year

follow-up study of children with ADHD. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1996;35:1193-1204.

25.

Biederman J, Newcorn J, Sprich S. Comorbidity of Attention Deficit

Hyperactivity Disorder With Conduct, Depressive, Anxiety, and Other Disorders.

Am j Psychiatry. 1991;148:564-577.

26.

Klorman R, Brumaghim JT, Salzman LF, et al. Effects of methylphenidate on

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder with and without

aggressive/noncompliant features. J Abnorm Psychol. 1988;97:413-422.

27.

Biederman J, Faraone SV, Keenan K, et al. Further evidence for family-genetic

risk factors in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Patterns of

comorbidity in probands and relatives in psychiatrically and pediatrically

referred samples. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1992;49:728-738.

28.

Brent DA, Perper JA, Goldstein CE, et al. Risk factors for adolescent suicide:

a comparison of adolescent suicide victims with suicidal inpatients. Arch Gen

Psychiatry. 1988;45:581-588.

29.

Biederman J, Faraone S, Keenan K, et al. Family genetic and psychosocial risk

factors in attention deficit disorder. Biol Psychiatry. 1989;25:145A.

30.

Swansom JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, et al. Clinical relevance of the primary

findings of the MTA: success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms

at the end of treatment. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40:168-179.

31.

The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-month randomized clinical trial of treatment

strategies for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Multimodal Treatment

Study of Children with ADHD. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1999;56:1073-1086.

32.

Spencer J, Biederman J, Mick E. Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder:

Diagnosis, Lifespan, Comorbidities, and Neurobiology. Ambulatory Pediatrics.

2007;7:73-81.

33.

Goldman S, Genel M, Bezman R, Slanetz P. Diagnosis and Treatment of

Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder in Children and Adolescents. JAMA.

1998;279:1100-1107.

34.

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition.

Washington, DC; American Psychiatric Association:1994.

35.

Morgan A, Hynd G, Riccio C, Hall J. Validity of DSM-IV ADHD predominately

inattentive and combined types: relationship to previous DSM diagnoses/subtype

differences. J Am Acad Child Adolsec Psychiatry. 1996;35:325-333.

36.

Paternite C, Loney J, Roberts M. External validation of oppositional disorder

and attention deficit disorder with hyperactivity. J Abnorm Child Psychol.

1995;23:453-471.

37.

Wolraich M, Hannah J, Pinnock T, et al. Comparison of diagnostic criteria for

attention-deficit hyperacitivty disorder in a country-wide sample. J Am Acad

Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1996;35:319-324.

38.

Sleator E, Ullman R. Can the physician diagnose hyperactivity in the office?

Pediatrics. 1981;67:13-17.

39.

Mitsis E, McKay K, Schulz K, et al. Parent-teacher concordance for DSM-IV

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in a clinic-referred sample. Child

Adolesc Psychiatry. 2000;39:308-313.

40.

Molina B, Pelham W, Blumenthal J, Galiszewski E. Agreement among teachers’

behavior ratings of adolescents with a childhood history of

attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Clin Child Psychol.

1998;27:330-339.

41.

Kramer T, Phillips S, hargis M, et al. Disagreement between parent and

adolescent reports of functional impairment. J Child Psychol Psychiatry.

2004;45:248-259.

42.

Geller B, Williams M, Zimerman B, Frazier J, Beringer L, Warner K. Prepubertal

and early adolescent bipolarity differentiate from ADHD by manic symptoms,

grandiose delusions, ultra-rapid or ultradian cycling. Journal of Affective

Disorders. 1998;51:81-91.

43.

Kiddie-Sads-Present and Lifetime Version (K-SADS-PL).

http://www.wpic.pitt.edu/ksads/default.htm. Accessed April 19, 2007.

44.

Achenbach T, Edelbrock L. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist 4-18 and 1991

Profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont;1991.

45.

Reynolds C, Kamphouse R. BASC: Behavior Assessment System for Children Manual.

Circle Pines, MN: American guidance Service; 1992.

46.

Brown TE. Brown ADD Scales for Children and Adolescents. San Antonio, TX:

Psychological Corp; 2001.

47.

Swanson, Nolan and Pelham (SNAP) Questionnaire (Swanson et al, 1983).

48.

Shaffer D, Fisher P, Dulcan M, et al. The second version of the NIMH Diagnostic

Interview Schedule for Children (DISC-2). J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1996;35:865-877.

49.

Quinn P, Wigal S. Perceptions of girls and ADHD: results from a national

survey. MedGenMed. 2004;6:2.

50.

Sharp WS, Walter J, Marsh W, Ritchie G, Hamburger S, Castellanos F. ADHD in

girls: clinical comparability of a research sample. J Am Acad Child Adolesc

Psychiatry. 1999;38:40-47.

51.

Biederman J, Faraone S, Milberger S, et al. Clinical correlates of ADHD in

females: findings from a large group of girls ascertained from pediatric and

psychiatric referral sources. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry.

1999;38:966-975.

52.

Carlson C, Tamm L, Gaub M. Gender differences in children with ADHD, ODD and

co-occurring ADHD/ODD identified in a school population. J Am Acad Child

Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1706-1714.

53.

Gaub M, Carlson C. Gender differences in ADHD: a meta-analysis and critical

review. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:1036-1045.

54.

The MTA Cooperative Group. A 14-Month Randomized Clinical Trial of Treatment

Strategies for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

1999;56:1073-1086.

55.

Wigal S, McGough J, McCracken J, et al. A laboratory school comparison of mixed

amphetamine salts extended release (Adderall XR) and atomoxetine (Strattera) in

school-aged children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder. J Atten

Disord. 2005;9:275:289.

56.

Arnold L. Alternative treatments for adults with attention-deficit

hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2001;931:310-341.

57.

Wigal S, Wigal T, Kollins S. Advances in Methylphenidate Drug Delivery Systems

for ADHD Therapy. Advances in ADHD. 2006;1:4-7.

To take the free, online CME post-test, go to www.mssmtv.org/psychweekly