Print Friendly

Calming the Storm: Psychodynamic Treatment of Panic Disorder

Fredric N. Busch, MD

Dr. Busch is a clinical associate professor of psychiatry at the Weill Cornell

Medical College in New York City.

Disclosure: Dr. Busch reports no affiliation with

or financial interest in any organization that may pose a conflict of interest.

Please

direct all correspondence to: Fredric N. Busch, MD, Clinical Associate Professor

of Psychiatry, Department of Psychiatry, Cornell University, 10 East 78th St,

Apt. 5A, New York, NY 10021; Tel: 212-734-0257; Fax: 212-734-0257; E-mail: [email protected].

Abstract

This article describes the limitations of current treatments for panic disorder.

Despite demonstrations of effectiveness of cognitive-behavioral and psychopharmacologic

treatments, many patients fail to respond to these interventions or have persistence

or recurrence of symptoms. Given the high costs and morbidity of panic disorder,

there is a need to continue to explore treatment options. Psychoanalytic approaches

are commonly used for panic disorder but have undergone little systematic study.

This article describes the psychoanalytic concepts involved in understanding panic

disorder, and proposes a manualized psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder

called panic-focused psychodynamic psychotherapy. A case example is used to demonstrate

some aspects of conducting treatment with this approach. This article also reviews

the limited systematic research on psychodynamic treatment of panic.

INTRODUCTION

Both

pharmacologic1-3 and cognitive-behavioral treatments4-6

of panic disorder have been found to be effective in the short-term treatment

of panic disorder. However, many patients fail to respond to or are unable to

tolerate these treatments.4-8 Relapse is frequent if medication is

discontinued before a prolonged maintenance phase.9-12 In addition,

questions remain about the long-term effectiveness of these interventions.4,13

In studies of routine care, patients frequently demonstrate persistent symptoms

and problems functioning.14 Finally, these treatments may not be as

effective in treating impairments associated with panic disorder, such as

occupational dysfunction, relationship difficulties, and diminished quality of

life.15,16 Given the high morbidity and health costs of this

disorder,17-20 it is important to develop the most effective

treatments for panic disorder and related impairments.

A

commonly used but not well-studied treatment for panic disorder is

psychodynamic psychotherapy. The potential value of this treatment is based on

the notion that panic patients have a psychological vulnerability to the

disorder associated with “personality disturbances, relationship problems,

difficulties tolerating and defining inner emotional experiences, and unconscious

conflicts about separation, anger and sexuality.”21 Psychodynamic

treatments focus more on these impairments than cognitive-behavioral and

psychopharmacologic treatments, potentially reducing vulnerability to panic

recurrence.21 The author of this article and colleagues developed a

psychodynamic formulation for panic disorder based on psychoanalytic theory,

systematic psychological assessments, and clinical observations to guide

treatment interventions.21-23 This article describes psychoanalytic

concepts as they relate to panic disorder, followed by a psychodynamic

formulation that weaves together neurophysiologic and psychological

vulnerabilities to panic.

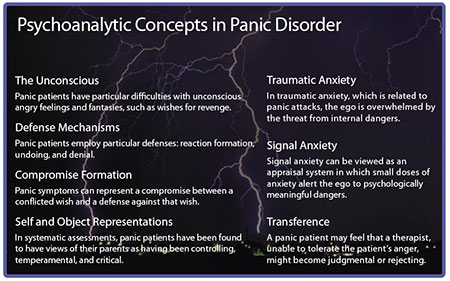

Psychoanalytic Concepts in Panic Disorder

The Unconscious

According

to psychoanalytic theory, symptoms are based at least in part on unconscious fantasies

and affects.24 For example, clinical and research observation

suggests that panic patients have particular difficulties with angry feelings

and fantasies, such as wishes for revenge.22,23,25 These wishes

represent a threat to important attachment figures, thus triggering anxiety.

Patients are often unaware of the intensity of these affects and the vengeful

fantasies that accompany them. Becoming aware of these aspects of mental life

and rendering them less threatening are important components of psychodynamic

psychotherapy.

Defense Mechanisms

Fantasies

and affects that are experienced as dangerous can be dealt with through the triggering

of defenses, that is, mental processes that disguise the fantasies or render

them unconscious.26 Clinical and research observations indicate that

panic patients employ particular defenses: reaction formation, undoing, and

denial.27 Reaction formation and undoing play a particular role for

panic patients in that they attempt to convert an angry affect into a more affiliative

one, diminishing the threat to an attachment figure. In reaction formation a

threatening feeling is replaced by its opposite; negative feelings of panic

patients are oftentimes replaced by concern and efforts to help others. In

undoing, a negative affect or fantasy is typically taken back in some way.

Denial represents a lack of recognition of the presence of a particular feeling

or fantasy, such as a patient reporting he was not angry even after someone had

done something hurtful to him. It is generally important to bring these

defenses to the patient’s attention as they maintain the patient’s avoidance of

exploring the frightening feelings and fantasies. For example, a patient who

follows the statement “I hate him” by “but I really love him” (an example of

undoing), is often trying to avoid the intensity of his angry feelings.

Compromise Formation

A

symptom can represent a compromise between a conflicted wish and a defense

against that wish.24 Teasing apart the components of this compromise

formation can help to understand the meaning of that symptom and the

unconscious factors that are triggering it. Thus, panic symptoms can include

the wish to be taken care of, a denial of anger through a focus on anxiety or

bodily symptoms, and an unconscious expression of anger in the coercive aspect

of pressuring others to help.

Self and Object Representations

Particular

self and object representations can trigger a susceptibility to certain

symptoms. In systematic assessments, panic patients have been found to have

views of their parents as having been controlling, temperamental, and critical.28,29

These expectations of the behaviors of others are internalized. In addition,

because of their predisposition to fearfulness, panic patients have a view of

others as essential to their safety and well-being. Recognizing these perceptions

of self and others can help panic patients understand the danger they

experience in communicating wishes to be taken care of as well as angry

feelings.

Traumatic and Signal Anxiety

Freud

distinguished between “traumatic” and “signal” anxiety.30 In

traumatic anxiety, which is related to panic attacks, the ego is overwhelmed by

the threat from internal dangers. Signal anxiety, on the other hand, can be

viewed as an appraisal system in which small doses of anxiety alert the ego to

psychologically meaningful dangers, such as potential disruptions in attachment

or the threat from vengeful feelings. Signal anxiety can trigger defenses that

act unconsciously to ward off potential dangers. In panic-focused psychodynamic

psychotherapy (PFPP), the therapist works with anxiety to help the patient

cognitively reappraise the degree of actual danger he is in.

Transference

In the

course of treatment, conflicts that the patient experiences as occurring with

others will often be mirrored in the relationship with the therapist. For

example, a panic patient may feel that a therapist, unable to tolerate the

patient’s anger, might become judgmental or rejecting. This phenomenon,

referred to as transference, can provide direct access to intrapsychic conflicts

and self-and-object representations that underlie panic symptoms. The safe

environment provided by a nonjudgmental and collaborative therapist aids in the

emergence of transference feelings and fantasies.

Psychodynamic Formulation for Panic Disorder

Busch

and colleagues21 and Shear and colleagues22 developed a

psychodynamic formulation for panic disorder based on neurophysiologic

predispositions, psychological findings, and psychoanalytic theory. The

formulation posits that certain individuals are susceptible to the onset of

panic disorder due to a predisposition to anxiety associated with a fearful

temperament described by Kagan and colleagues.31 Because of their

anxiety, children with this predisposition tend to develop a fearful dependency

on others, feeling that the parents must be present at all times to provide a

sense of safety. In addition, the dependency on others is a narcissistic

humiliation for these children, because feelings of safety often require the

caregiver’s presence. This fearful dependency can develop from a biochemical

vulnerability or from an early relationship in which the children experience

frightening threats or behavior by caregivers. In either case, parents are

perceived as “unreliable,” and prone to abandonment and rejection of the child.

In

response to perceived rejection or unavailability, and due to the narcissistic

injury of dependency, the child becomes angry at his caregivers. This anger is

experienced as a danger, as it could potentially damage the relationship with

the caretakers upon whom the child depends, increasing the threat of loss and

fearful dependency. Thus, a vicious cycle of fearful dependency and anger can

occur. The vicious cycle is triggered again in adulthood, when the individual

experiences or perceives a threat to important attachment figures. Signal

anxiety and defenses are triggered, such as undoing, reaction formation, and

denial, in an attempt to reduce the threat from anger and maintain attachments.

However, due to the degree of threat from these fantasies, as well as

immaturity of the signal anxiety mechanism, the ego is overwhelmed and panic

levels of anxiety result. Panic attacks further avert the experience of anger

and compel attention from others to attend to the patient’s distress.

Recent

developments in psychoanalytic theory elucidate another component of the

process of panic onset and persistence. Mentalization describes the ability to

understand self and others with regard to motives, desires, and feelings.32

Panic patients may have either a diminished capacity for mentalization in

general or specific disruptions in this ability caused by conflicts regarding

dependency and angry feelings and fantasies. This lack of access to feelings and

fantasies can be viewed as unconscious efforts to “not know” about conflicts in

order to avoid the threat to attachment.33 Greater introspective

access and mentalization about emotional states of the self and others helps to

relieve these dangers. This can allow panic patients to develop voluntary

“top-down” cognitive control over emotional reactions by selectively inhibiting

and modifying them.

Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy

Overview of PFPP

As

opposed to more traditional open-ended psychodynamic treatment and

psychoanalysis, PFPP focuses on panic symptoms and the dynamics associated with

panic disorder. Material in the sessions other than panic symptomatology is

ultimately related to the dynamics of panic. The treatment follows the overall

course of identifying the meanings of panic symptoms; calling attention to

defenses that inhibit awareness of frightening feelings, conflicts, and

fantasies; and, once made conscious, rendering these feelings less threatening

or less toxic. Psychoanalytic techniques of clarification, confrontation, and

interpretation are employed in this process.

Phase I

In

phase I, the therapist works to identify the specific content and meanings of

the panic episode. In addition, the patient and therapist examine the stressors

and feelings surrounding the onset and persistence of panic. The patient’s

developmental history is reviewed to delineate specific vulnerabilities that

may have led to panic onset, such as particular representations of parents,

traumatic experiences, and difficulty expressing and managing angry feelings.

The therapist’s nonjudgmental stance aids the patient in bringing forth

fantasies and feelings that may have been unconscious or difficult to tolerate,

such as vengeful wishes or abandonment fears. The information is used to

identify the presence of intrapsychic conflicts surrounding anger, separation,

and sexuality. The goal of this phase is reduction in panic symptoms.

Phase II

Phase

II seeks to address the dynamics that lead the patient to be vulnerable to

panic onset and persistence. As noted above, these typically include conflicts

surrounding anger recognition and management, separation, and fears of loss or

abandonment. These dynamics are addressed as they emerge in the patient’s

feelings and fantasies about relationships in their present and past and in the

transference relationship with the therapist. The meanings of symptoms and the

employment of defenses also continue to play a role in identifying the dynamic

constellations. Improved understanding of these conflicts helps patients to

prevent the development of the vicious cycle described in the formulation

above, reducing vulnerability to panic disorder recurrence.

Phase III

The

termination phase provides an opportunity to work with the patient’s conflicts

with anger and separation as they emerge in the context of ending treatment.

Patients can experience and articulate their feelings about loss directly with

the therapist. This increased awareness and understanding allows for better

management of these feelings and the capacity to avert the development of more

severe panic states. An ability to express anger in ways that feel safe is an

important development in the treatment. Increased assertiveness and the

capacity to communicate about conflicts in relationships improves quality of

life and reduces panic vulnerability.

Conducting Treatment with PFPP

Psychoanalysis

and psychodynamic psychotherapy have typically been thought to be indicated for

patients who enter treatment with a particular set of qualities that includes

being verbally skilled, psychologically minded, and curious about the origins

of their symptoms. Panic patients, however, with their tendency to experience conflicts

and affects as focused in their bodies, have limited verbal access to their

intrapsychic life and may be frightened to pursue the origins of their

problems. The author of this article and colleagues have found that patients

without these skills can obtain relief of symptoms from PFPP.34,35 A

case example illustrates some of the aspects of treatment with this approach.

Engaging the Patient

Several

factors enable PFPP to work as a short-term treatment or as an intervention

that can help people with little exposure to psychotherapy. This treatment

includes a component of psychoeducation, not only about panic disorder, but

also about the psychodynamic model and how it operates. In early sessions the

therapist focuses on exploring the circumstances and feelings preceding panic

onset. Patients become engaged with the treatment as they see the relationship

between their symptoms, the stresses preceding onset, the feelings surrounding

panic, and their developmental history.

Ms. A

was a 43-year-old married woman with two children who described the onset of

panic attacks 1 month prior to consultation. She presented with a symptom

picture that met criteria for panic disorder along with mild symptoms of

depression. She recalled a series of panic attacks just after leaving home for

college, but these had resolved spontaneously. At first Ms. A described her

panic as having emerged out of the blue. However, on exploration the therapist

learned that the initial panic attack occurred after an intense conflict with her

15-year-old daughter, the older of two siblings. Ms. A struggled with how to

manage her daughter and saw herself as unable to set limits. She viewed limit

setting as being “too mean.” Ms. A quickly grasped that her panic was likely related

to these conflicts and her difficulty managing them. She noted that she was

“not very assertive” and always had difficulty confronting others.

Following

this initial link of the onset of symptoms to family conflicts, Ms. A became

very curious about the sources of her problems. The discussion about her

daughter reminded her of her problems with her alcoholic father, who had a

severe temper problem. The therapist wondered if Ms. A was frightened of

expressing any disagreement with him.

Ms. A

responded: “Yes, I think I was scared of that. I am always trying to be nice to

people. I think that will get them to like me. But I am not sure that it is

really helping my daughter to do that.” In this instance, Ms. A was describing

reaction formation, in which her anger toward her daughter was converted into

becoming “too nice.” She then noted: “I realize I should be setting better

limits. Yesterday when I stood my ground with her I felt so much better.”

This

information, presented in the first two sessions of Ms. A’s treatment, already

provided valuable insights into the origins of her panic disorder. Such

triggers included the stress of the conflict with her daughter, difficulties

with her management of limit setting, and her fears of getting angry.

Transference

As

treatment progresses, the therapist has more opportunities to explore conflicts

as they emerge in transference. Oftentimes, these occur in the context of angry

feelings toward or separation fears from the therapist.

In a

later session, Ms. A complained about an incident with her daughter, and

referred to her as “difficult.” The therapist remarked that her view of her

child had partly to do with her own behavior, because she was aware that when

she set proper limits, her child responded. Although she did not state this during

the session, she experienced her therapist’s comments as suggesting she was a

bad mother, unwilling to take responsibility for her parenting. She became

anxious after the session. That evening she asked her husband to comfort her

but he responded that he had had a stressful day and wanted to read the paper.

Subsequently, she had the onset of a panic attack. The following session the

therapist and patient were able to determine that the patient was quite angry

at her therapist and husband, and her conflict about her anger triggered the

attack.

Working Through and Termination

Working

through involves identifying the presence of conflicts in different areas of

the patient’s life, allowing increased understanding of feelings and fantasies.

These areas include the patient’s relationship with the therapist and others as

well as the patient’s internal fantasy life. For example, Ms. A realized her

unassertiveness came from several sources, including fear of her temperamental

father, fear of her sister who was more aggressive and bolder, and identification

with her mother who was also unassertive and would not confront her father

about problems. Each of these instances helped to elucidate the patient’s worry

that asserting herself would lead to disruptions in her relationships. In fact,

she felt that being the “nice girl” maintained others’ interest in her.

Termination

provides an important opportunity for looking at these conflicts directly in

the relationship with the therapist. Anger at and fear of losing the therapist

will often intensify at this point, highlighting conflicts that emerged earlier

in the treatment. For example, in short-term (24-session) PFPP treatments,

patients were typically pleased about the progress they had made, but were

often able to express concern and frustration with the therapist about ending

treatment.34,35

Research on Psychodynamic Treatment of Panic

Disorder

As is

generally the case with psychodynamic psychotherapy or psychoanalysis, there

have been few systematic studies using manualized treatments for panic

disorder. Wiborg and Dahl36 conducted a randomized, controlled trial

of a manualized form of psychodynamic psychotherapy along with clomipramine

compared to clomipramine alone. The 3-month weekly psychotherapy combined with medication

reduced relapse at 18 months compared to patients treated with clomipramine

alone (9% vs. 91%).

An open

trial of PFPP was conducted with this approach consisting of 24 sessions over a

12-week period.34,35 Of 21 patients meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV)37

criteria for panic disorder, there were 4 dropouts. Sixteen of the remaining 17

patients had remission of panic and agoraphobia, as well as significant

quality-of-life improvements. These gains were maintained at 6-month follow up.

Notably, the 8 subjects who had also had comorbid major depressive disorder

experienced relief of these symptoms as well. Although not a randomized

controlled trial, the study suggested that PFPP can provide significant relief

of panic symptoms. A randomized controlled trial comparing PFPP to applied

relaxation therapy has been completed, but as of this writing the results have

not been published.

Conclusion

Given

that panic disorder remains a significant public health problem, it is

important to continue to develop approaches to its treatment. PFPP is a useful

alternative or adjunct to cognitive-behavioral therapy and/or medication. PFPP

addresses intrapsychic conflicts, defense mechanisms, developmental factors,

and transference issues not likely to be focused on in other treatments. Thus,

this approach may affect psychological factors that lead to vulnerability to

recurrence of panic or other difficulties associated with panic disorder. An

open trial demonstrated positive results. A completed placebo-controlled trial

should shed further light on the effectiveness of this treatmentmedical costs.

References

1. Otto MW, Tuby KS, Gould RA, McLean RY,

Pollack MH. An effect-size analysis of the relative efficacy and tolerability

of serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors for panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry.

2001;158(12):1989-1992.

2. Bakker A, van Balkom AJ, Spinhoven P.

SSRIs vs. TCAs in the treatment of panic disorder: a meta-analysis. Acta

Psychiatr Scand. 2002;106(3):163-167.

3. Wilkinson G, Balestrieri M, Ruggeri M,

Bellantuono C. Meta-analysis of double-blind placebo-controlled trials of

antidepressants and benzodiazepines for patients with panic disorder. Psychol

Med. 1991;21(4):991-998.

4. Barlow DH, Gorman JM, Shear MK, Woods

SW. Cognitive-behavioral therapy, imipramine, or their combination for panic

disorder: A randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2000;283(19):2529-2536.

Errata in: JAMA. 2000;284(19):2450. JAMA. 2001;284(20):2597.

5. Craske MG, Brown TA, Barlow DH.

Behavioral treatment of panic: a two-year follow-up. Behav Ther.

1991;22(3):289-304.

6. Craske MG, DeCola JP, Sachs AD,

Pontillo DC. Panic control treatment for agoraphobia. J Anxiety Disord.

2003;17(3):321-333.

7. Marks IM, Swinson RP, Basoglu M, et

al. Alprazolam and exposure alone and combined in panic disorder with

agoraphobia. A controlled study in London and Toronto. Br J Psychiatry.

1993;162:776-787.

8. Shear MK, Maser JD. Standardized

assessment for panic disorder research. A conference report. Arch Gen

Psychiatry. 1994;51(5):346-354.

9. Mavissakalian M, Michelson L. Two-year

follow-up of exposure and imipramine treatment of agoraphobia. Am J

Psychiatry. 1986;143(9):1106-1112.

10. Nagy LM, Krystal JH, Woods SW, Charney

DS. Clinical and medication outcome after short-term alprazolam and behavioral

group treatment in panic disorder. 2.5 year naturalistic follow-up study. Arch

Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46(11):993-999.

11. Noyes R Jr, Garvey MJ, Cook BL.

Follow-up study of patients with panic disorder and agoraphobia with panic

attacks treated with tricyclic antidepressants. J Affect Disord.

1989;16(2-3):249-257.

12. Pollack MH, Otto MW, Tesar GE, Cohen

LS, Meltzer-Brody S, Rosenbaum JF. Long-term outcome after acute treatment with

alprazolam and clonazepam for panic disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol.

1993;13(4):257-263.

13. Milrod B, Busch F. Long-term outcome of

panic disorder treatment. A review of the literature. J Nerv Ment Dis.

1996;184(12):723-730.

14. Vanelli M. Improving treatment response

in panic disorder. Primary Psychiatry. 2005;12(11):68-73.

15. Markowitz JS, Weissman MM, Ouellette R,

Lish JD, Klerman GL. Quality of life in panic disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry.

1989;46(11):984-992.

16. Rubin HC, Rapaport MH, Levine B, et al.

Quality of well-being in panic disorder: the assessment of psychiatric and

general disability. J Affect Disord. 2000;57(1-3):217-221.

17. Katon W. Panic disorder: relationship

to high medical utilization, unexplained physical symptoms, and medical costs. J

Clin Psychiatry. 1996;57(suppl 10):11-18.

18. Swinson RP, Cox BJ, Woszczyna CB. Use

of medical services and treatment for panic disorder with agoraphobia and for

social phobia. CMAJ. 1992;147(6):878-883.

19. Fyer AJ, Liebowitz MR, Gorman JM, et

al. Discontinuation of alprazolam in panic patients. Am J Psychiatry.

1987;144(3):303-308.

20. O’Sullivan G, Marks I. Follow-up

studies of behavioral treatment of phobic and obsessive compulsive neurosis. Psych

Annals. 1991;21(6):368-373.

21. Busch FN, Cooper AM, Klerman GL,

Shapiro T, Shear MK. Neurophysiological, cognitive-behavioral and

psychoanalytic approaches to panic disorder: toward an integration. Psychoanalytic

Inquiry. 1991;11(3):316-332.

22. Shear MK, Cooper AM, Klerman GL, Busch

FN, Shapiro T. A psychodynamic model of panic disorder. Am J Psychiatry.

1993;150(6):859-866.

23. Milrod BL, Busch FN, Cooper AM, Shapiro

T. Manual of Panic-Focused Psychodynamic Psychotherapy. Washington, DC:

American Psychiatric Press; 1997.

24.

Breuer J, Freud S. Studies on hysteria (1895). In: Strachey J, trans and ed. The

Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol

2. London, England: Hogarth Press; 1959:1-183.

25. Kleiner L, Marshall WL. The role of

interpersonal problems in the development of agoraphobia with panic attacks. J

Anxiety Disorders. 1987;1(4):313-323.

26. Freud S. The neuropsychoses of defence

(1894). In: Strachey J, trans and ed. The Standard Edition of the Complete

Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol 3. London, England: Hogarth

Press; 1959:45-61.

27. Busch FN, Shear MK, Cooper AM, Shapiro

T, Leon A. An empirical study of defense mechanisms in panic disorder. J

Nerv Ment Dis. 1995;183(5):299-303.

28. Parker G. Reported parental

characteristics of agoraphobics and social phobics. Br J Psychiatry.

1979;135:555-560.

29. Arrindell WA, Emmelkamp PM, Monsma A,

Brilman E. The role of perceived parental rearing practices in the aetiology of

phobic disorders: a controlled study. Br J Psychiatry. 1983;143:183-187.

30. Freud S: Inhibitions, symptoms and

anxiety (1926). In: Strachey J, trans and ed. The Standard Edition of the

Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud. Vol 20. London, England:

Hogarth Press; 1959:77-174.

31. Kagan J, Reznick JS, Snidman N, et al.

Origins of panic disorder. In: Ballenger JC, ed. Neurobiology of Panic

Disorder. New York, NY: Wiley; 1990:71-87.

32. Fonagy P. Thinking about thinking: some

clinical and theoretical considerations in the treatment of a borderline

patient. Int J Psychoanal. 1991;72(pt 4):639-656.

33. Rudden MG, Milrod B, Aronson A, Target

M. Reflective functioning in panic disorder patients: clinical observations and

research design. Psychoanalytic Inquiry. In press.

34. Milrod B, Busch F, Leon AC, et al. A

pilot open trial of brief psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder. J

Psychother Prac Res. 2001;10(4):239-245.

35. Milrod B, Busch F, Leon AC, et al. An

open trial of psychodynamic psychotherapy for panic disorder: a pilot study. Am

J Psychiatry. 2000;157(11):1878-1880.

36. Wiborg IM, Dahl AA. Does brief dynamic

psychotherapy reduce the relapse rate of panic disorder? Arch Gen Psychiatry.

1996;53(8):689-694.

37. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of

Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association;

1994.