Growing Pains: Improving Treatment for Adolescent Bipolar Disorder

| October 16, 2006 |

Robert L. Findling, MD |

Director, Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, University Hospitals of Cleveland, Professor of Psychiatry

and Pediatrics, Case Western Reserve University

This interview was conducted by Peter Cook, on August 31, 2006.

Introduction

Dr. Robert Findling’s interest in bipolar disorder (BD) was sparked in 1994, shortly after he joined the faculty

at Case Western Reserve. “At that time,” he says, “Case Western Reserve had a well-established program

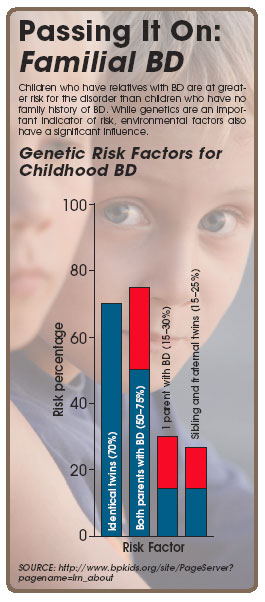

for treating adult bipolarity. BD is heritable so, unsurprisingly, we discovered that a good deal of the offspring of our

adult patients were also having mood-related difficulties. My being brought face to face with these young patients, in

conjunction with the paucity of data on BD in children and adolescents, convinced me of the necessity of researching and

treating this disorder in this population.” While there are inadequate data on the prevalence of BD in the young,

Dr. Findling believes it’s actually reasonably common in clinical settings. It’s also clear that, despite the

lack of data linking child and adolescent BD to adult BD, the more severe expressions of BD are lasting, malignant, and

pervasive.

Presentation

“What gets a lot of these youngsters in trouble—and thus what precipitates their parents bringing them to

a psychiatrist—is aggression,” Dr. Findling says. However, he further points out that dysfunctional and disruptive

behavior and irritability aren’t specific enough criteria to help with diagnosis. Data from his group suggest that

the symptoms that best characterize BD in the young are abnormally elevated mood and rapid fluctuations to and from abnormally

elevated mood. “It’s interesting,” he says, “that a lot of youngsters don’t get into their

worst trouble during periods of elevated mood, so elevated mood isn’t what they get brought in for. The most distinguishing

characteristic of the disorder is one which parents aren’t very likely to identify as the most serious problem.”

Recent data also indicate that, compared to adults with BD, children and adolescents with BD spend significantly less

time in a depressed state.

Diagnosis

Dr. Findling acknowledges that there isn’t yet a strong clinical consensus on whether BD

is a valid diagnosis in children and adolescents, particularly in youths with less prototypic manifestations. He stresses

that this is all the more reason that more research needs to be done in this area.

The lack of definitive criteria and the idiosyncrasies of its presentation make BD particularly

difficult to diagnose in the young. “There’s simply no substitution for taking time with the patient,” Dr. Findling says. “This

diagnosis cannot be made quickly.” He explains that spontaneous mood episodes—as opposed to behavioral manifestations—are

of particular diagnostic importance. “All things being equal, BD is a mood disorder, and mood disorders and mood

symptomatology should be associated with a characteristic group of symptoms.”

If a clinician believes a young patient might have BD, he or she ought to ask the parents about

grandiosity and abnormally elevated mood, even though these might not be associated with the parents’ main concerns. “The other thing

to focus on is longitudinal course,” Dr. Findling says. “Most youngsters don’t suddenly wake up one morning

with a high level of impairment, so you really want to pay close attention to symptom evolution.” Finally, due to

the heritability of BD, a careful and meticulous assessment of family history—beyond merely asking whether there’s

a history of diagnosed BD in the family—is essential.

Also of note, it can be quite difficult to isolate comorbid disorders in children with BD. As mood episodes often include

symptoms similar to those found with hyperactivity, anxiety, and OCD, clinicians must be very meticulous. Dr. Findling

suggests only diagnosing comorbid disorders if they present during euthymia.

Treatment

Today, there is a great deal more treatment data regarding BD in children and adolescents than

ever before, and more research is being done. However, there’s still an absence of double-blind data. “The evidence currently suggests

that mood stabilizers are frontline treatment for this patient population,” Dr. Findling says. “Further, there’s

a growing consensus—reflecting the available evidence—that, although 1 mood stabilizer gets a youngster with

BD better, 2 are usually required to get him or her fully well.”

Antipsychotics are also used, and a growing body of evidence suggests their effectiveness for youths

with BD. “We

generally stick with the atypicals,” Dr. Findling says, “because that’s where the most data lie. Often,

the families are nervous about their child taking an antipsychotic, so patient and family being fully informed about the

potential risks and benefits of different treatment choices is also an important consideration.” Dr. Findling will

soon be starting definitive trials on lithium for children and adolescents with BD, and he’s hopeful that this will

prove a worthwhile avenue of treatment as well.

Behavioral interventions also play a role, particularly in less severe expressions. Again, however,

there’s a lack

of definitive data on efficacy.

Dr. Findling stresses that it’s important to remember that there are only scant data about the less extreme expressions

of bipolar illness in this patient population, and how to treat them. “A key area for future research is the early

identification of prodromal kids versus more severely impaired kids,” Dr. Findling says. “It appears that less-impaired,

putatively prodromal kids are the ones that are most frequently presenting to clinical settings. This is why we’ve

been focusing so much of our efforts on patients with cyclotaxia—that is, the prodromal stages of cyclic mood disorders

in genetically at-risk children. Our hope is that early and accurate identification might help us prevent more extreme

expressions of BD.”

Conclusion

“We’ve made a lot of progress in diagnosing and treating BD in youngsters,” Dr. Findling says. “That’s

the good news. The bad news is, we’ve still got a lot of ground to make up.”

Disclosure: Dr. Findling has been a consultant for Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb,

Celltech-Medeva, Forest, GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, New River, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Sanofi-Aventis, Shire, Solvay, and

Wyeth; has received research or grant support from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Celltech-Medeva, Forest,

GlaxoSmithKline, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, New River, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Shire, Solvay, and Wyeth; and has sat

on the speaker’s bureau for Shire.

Source: http://www.bpkids.org/site/PageServer?

pagename=lrn_about