Anxiety’s Legacy: The Long-Term Outcomes of Behavioral Inhibition

Jerrold F. Rosenbaum, MD

Psychiatrist-in-Chief, Massachusetts General Hospital, Chair, MGH Executive Committee on Research

(ECOR), Stanley Cobb Professor of Psychiatry, Harvard Medical School

This interview was conducted by Peter Cook on July 13, 2006.

Introduction

Over 20 years ago, in reviewing the work of Jerome Kagan on infants, toddlers, and young children with behavioral inhibition

to the unfamiliar (BI), Dr. Jerrold Rosenbaum noticed striking similarities between the temperamental fearfulness of these

children in unfamiliar settings and descriptions of the childhood behavior of adult patients with anxiety disorders, in

particular agoraphobia. In adults with agoraphobia, there was a high prevalence of childhood school phobia and separation

anxiety reported, and Dr. Rosenbaum wondered whether these childhood fears might be linked to BI and could be viewed as

risk factors for later development of anxiety disorders.

“We also noted there was physiologic evidence of increased arousal in the children with behavioral inhibition,” Dr.

Rosenbaum notes, “and we wondered if they might have noradrenergic or other dysregulation related to risk for adult

anxiety.”

Thus began a multi-faceted series of longitudinal studies conducted in collaboration with Dr. Joseph Biederman and the

Biederman lab (the Pediatric Psychopharmacology Division) at MGH that continues to this day.

“Our studies have mirrored the trends of psychiatry in America over the last quarter century,” Dr. Rosenbaum

says. “When we began, modern psychopharmacology and evidence-based medicine were taking hold. As our studies have

progressed and the cohorts have aged, we’ve been able to take advantage of new technologies in genetics to explore

the heritability of risk for anxiety disorders, and now, with advances in neuroimaging, we’ve begun to look at the

pathophysiology of anxiety disorders as well.”

Early Studies

Dr. Rosenbaum and colleagues began by checking for higher rates of behavioral inhibition in children whose parents had

anxiety disorders.

“We originally recruited parents with panic disorder and agoraphobia, and their children,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. “We

found that behavioral inhibition was indeed more common in children whose parents had these anxiety disorders. In addition,

if parents had a history of childhood anxiety disorders, their children were more prone to the fearful temperament. It

might sound obvious, but the hypothesis that rose from our findings was that some people are born with a predisposition

to increased arousal and a fear of novel stimuli that leads to sustained vulnerability to anxiety disorders.”

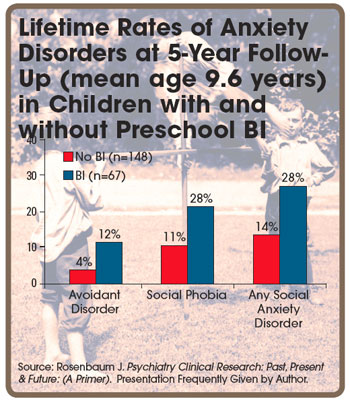

As the study continued, this hypothesis was born out: children who had behavioral inhibition were significantly more likely

to develop anxiety disorders later in childhood, in particular social anxiety disorder.

Genetics

As Dr. Rosenbaum and colleagues continued to look at their large, family cohort (which eventually

totaled 250 families), it became very clear that risk for anxiety disorders and behavioral inhibition was transmitted.

Interestingly, the heritability of behavioral inhibition has shown to be 50%–70% higher than anxiety disorders.

“Newer technologies have now enabled us to begin identifying specific genes implicated in this,” Dr. Rosenbaum

says. “My colleague, Dr. Jordan Smoller has identified genetic polymorphisms linked with the heritability of behavioral

inhibition and panic disorder, genes that have been associated with fear behaviors in mice, and now with evidence that

they’re relevant in humans, as well.”

Neuroimaging

Another of Dr. Rosenbaum’s colleagues, Dr. Carl Schwartz, has used fMRI to examine the brains

of a related study cohort.

“Dr. Schwartz found increased amygdalar reactivity in young adults who had been identified, early on, as behaviorally

inhibited,” Dr. Rosenbaum explains.

The amygdala has long been associated with fear responses. In other research, Dr. Scott Rauch and colleagues found, in

addition to increased amygdalar activity, associated decreases in the ventral medial pre-frontal cortex (vmPFC) and the

hippocampus in patients with both PTSD and panic disorder.

“Dr. Rauch’s hypothesis is that the vmPFC and hippocampus might not be implementing sufficient top-down control

on the fear-related signals being generated in the amygdala,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. However, further tests are being

planned to assess whether differences in these areas are risk factors or essential elements of pathophysiology.

Treatment

“Now we know that some people are predisposed to anxiety disorders,” Dr. Rosenbaum says, “and,

further, that there is likely a biological basis for these disorders. The next question is: can early identification

of risk make a difference in long-term outcome?”

The tentative answer appears to be “yes.” Another colleague of Dr. Rosenbaum’s,

Dr. Dina Hirshfeld, recently published the results of a study on early intervention for children with behavioral inhibition

and anxiety, and the results were quite positive. Ten to twelve sessions of cognitive therapy, education, and family-based

intervention produced, at a 1 year follow up, significantly reduced rates of symptoms and lower likelihood of meeting

the criteria for anxiety disorders. Further follow-ups will indicate whether this intervention has long-term efficacy.

“We have wondered whether a pharmacological intervention could be devised as well,” Dr. Rosenbaum says. “We

suspect that increased activity in the amygdala is partially responsible for behavioral inhibition and anxiety disorders.

Might a drug that suppressed that over-activity in younger children with behavioral inhibition prevent them from later

developing anxiety disorders? We just don’t know yet.”

Conclusion

Dr. Rosenbaum’s longitudinal study of children at risk for anxiety disorders has been going

on for over 20 years, during which time he and his colleagues have made a number of breakthroughs in understanding the

incidence, genetics, treatment, and pathophysiology of anxiety disorders and BI in the children of parents with anxiety

disorders. They have further brain imaging studies planned, and will continue to look into the efficacy of early interventions.

And, as they have done, they will continue to bring new breakthroughs in psychiatric science to bear in understanding

our most pervasive psychiatric disorders.

Disclosure: Dr. Rosenbaum reports no affiliation with or financial interests in any organization that may pose a

conflict of interest.