Quality of Life: The Missing Piece of the Diagnostic Puzzle

Mark H. Rapaport, MD

Chairman, Department of Psychiatry, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Vice Chairman and Professor in Residence, Department of Psychiatry and Biobehavioral Sciences, David Geffen School of Medicine

For patients with mood and anxiety disorders, there is often a gap between symptoms and quality of life. It is a gap that Dr. Rapaport is particularly mindful of.

“We have to go beyond treating only some of the manifest signs and symptoms of the syndrome, be it panic disorder or social phobia or PTSD,” he says. “We need to realize that though we may use a certain set of descriptive criteria to define that syndrome, the syndrome itself has consequences that go well beyond just the signs and symptoms. In treatment, one has to address the consequences as well as the signs and symptoms. One of the challenges we face is that how we think about treatment is truly based on what has been defined in the DSM or on a rating scale, and we do not appreciate the impact of anxiety and mood disorders on quality of life or functioning.”

Functioning and Quality of Life

The picture is further complicated because, Dr. Rapaport believes, clinicians do not always appreciate how a person’s perception of his or her own quality of life can be drastically discordant with how well he or she functions on a day-to-day basis. It is one of the reasons why there can be a disconnection between objective measures of functioning and patients’ perceptions of what their lives are like. In these cases, an assessment of objective functioning is essential. Social phobias, for instance, often have very early onset, and as a result, those who suffer from them might perceive their quality of life as significantly higher than a more objective, experienced observer.

In Dr. Rapaport’s words, “they just do not know what they are missing.” In such a situation, the clinician needs to educate the person as they get better in order to help them develop the skills that they never had the opportunity to learn.

“Part of it,” Dr. Rapaport says, “is helping them understand that there are many more options available to them than they ever realized. Patients with anxiety-restricted function can sometimes become resigned to a life not lived to its fullest.” While some patients with restricted function might rate their quality of life as fair to good, many patients demonstrate good functioning, but rate their quality of life as quite bad.

Dr. Rapaport cites a patient he treated with severe PTSD and secondary depression: “She was a relatively successful senior academic administrator. She seemed like a regular, high-functioning adult, but she was bare-knuckling it through every single day. To an external observer who did not know her, she was functioning quite well, but she could tell you that the quality of her life was absolutely abysmal.” After stabilizing her primary symptoms, Dr. Rapaport focused on helping her regain quality into her life. The treatment was a success, but as Dr. Rapaport stresses, “we would not have reached that point with just symptoms and functioning. It took an understanding of what her life was really like.”

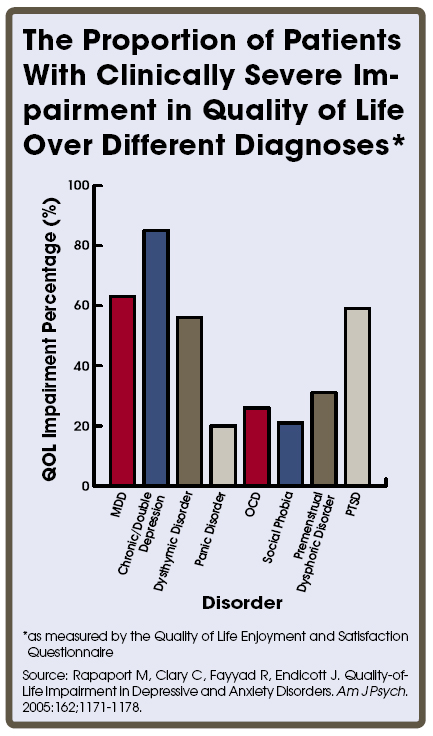

Dr. Rapaport and his colleagues have been collecting data for several years on every single patient examined at their practice with an aim to assess the relationship between psychiatric syndromes, functioning, and quality of life. They use Dr. Jean Endicott’s short form of the QS2, Quality of Life and Satisfaction Questionnaire. Although they have not done the definitive data analysis yet, the wider perspective offered by their in-depth assessments are already reshaping some of their programs where the degree of improvement in quality of life and functioning is not meeting their standards. For example, he points out that while it is relatively easy to get rid of the symptoms of a panic attack, patients with panic disorders continue suffering anticipatory anxiety (often extreme) even in the absence of actual panic attacks. Their symptoms may go away, but their quality of life does not improve.

It is important for physicians to remember that every interaction with a patient, regardless how short the interaction is, has therapeutic value and is an opportunity to reinforce psychotherapeutic principles and concepts with that patient. As Dr. Rapaport says, “there is a tremendous opportunity for people in psychiatry to do more. One of the problems in psychiatry is accepting being relegated to just prescribing medicines. We are a little too focused on merely signs and symptoms, and we do ourselves and our patients a disservice by not going farther.”