Print Friendly

Improving Diagnostic Accuracy—Bipolar Disorder

S. Nassir Ghaemi, MD, MPH

Dr. Ghaemi is Associate Professor of Psychiatry and Public Health

Director, Bipolar Disorder Research Program

Emory University Dept of Psychiatry, The Emory Clinic

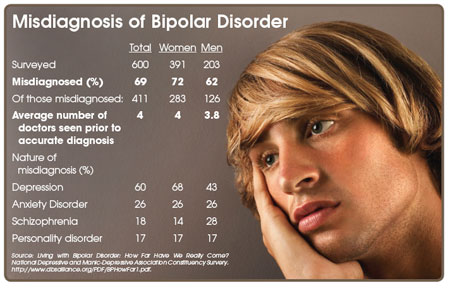

Dr. Ghaemi and colleagues have performed studies as recently as 2001 demonstrating that up to 40% of patients with bipolar disorder are initially misdiagnosed as having unipolar depression. And, aside from the prolonged suffering of patients being misdiagnosed, and thus mis-prescribed, there’s real danger in this collective spot-blindness. Dr. Ghaemi explains: “a subgroup of patients fall under the kindling model—the more episodes they have, the more episodes they will have. Intervention in those cases likely needs to happen sooner rather than later.”

When asked to identify why bipolar disorder is so under-diagnosed, Dr. Ghaemi presents four possible contributing factors.

- The Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition definition of bipolar disorder requires the clinician to diagnose evidence of mania, as well as depressive symptoms. This is problematic, because, typically in patients with bipolar disorder, depression presents more frequently, and for longer periods of time, than does mania.

“Depression is the primary morbidity,” Dr. Ghaemi says, “So it is automatic that many people with bipolar disorder are going to get diagnosed with depression, especially in the primary care setting.”

- The opacity of mania is another roadblock to accurate diagnosis. Over 50% of people with mania are not aware of their own manic symptoms, even during acutely manic episodes. Dr. Ghaemi stresses the importance of getting a family history and acquiring outside information on patients.

Dr. Ghaemi belives that “in today’s managed-care oriented settings, a physician might rule out bipolar disorder simply on the basis of patient self-report; that is just not sufficient.”

- Diagnosing bipolar disorder is further confounded by the prevailing winds of psychiatric treatment.

“We live in an antidepressant era. Fifteen years of mass-marketing to both physicians and patients has left its mark,” Dr. Ghaemi says.

Both patients and clinicians are oriented toward familiar antidepressants (which do, often, have many pluses, including familiarity with indications and relatively few side-effects), but are not fully acquainted with the mood-stabilizing treatments often necessary to treat bipolar disorder.

- Dr. Ghaemi cites the various types of bipolar disorder as an added complication for clinicians. Type 2 bipolar patients, for example, present with hypomania, however, Dr. Ghaemi points out that “these hypomanic episodes are quite brief—on the order of days to weeks at most—and it can be very difficult for patients to distinguish those brief periods from their normal personality or eurythmia.”

Again, outside source information is key.

The underdiagnosis of bipolar disorder serves to remind clinicians that there is more to diagnosis than identifying a patient’s present symptoms.

“We know that is not how you diagnose schizophrenia,” Dr. Ghaemi says. “But we have yet to learn that you do not diagnose depression just because the patient is currently depressed. Physician’s have to pay attention to the course of the illness, the family history, and the treatment response, as has been the traditional approach in psychiatric nosology, but this has not filtered down to daily clinical diagnostic practice. Hence unipolar depression is over-diagnosed, and bipolar disorder is under-diagnosed.”