Print Friendly

New Research Into the Genetic Risk Factors of Schizophrenia and Bipolar Disorder

Professor of Psychiatry and Human Genetics

University of Chicago

This interview was conducted on March 19, 2007 by Peter Cook.

Introduction

Dr. Elliot Gershon has been studying the genetics of bipolar disorder and schizophrenia ever since he finished his residency,

over 35 years ago. His original focus on these two disorders stemmed from a desire to improve understanding of (and thus,

eventually treatment for) two of the most prevalent and debilitating psychiatric illnesses, not from a belief that bipolar

disorder and schizophrenia shared proximal causes. Recent advances in genetics have, however, bestowed a retroactive providence

on Dr. Gershon’s choice of disorders to study. “Over the last few years, linkage scans have allowed researchers

to identify specific areas of the genome that likely contain a gene for a particular illness,” Dr. Gershon says. “We’ve

been surprised to discover that several regions of the genome are implicated in both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.” Linkage

scans, in essence, look for chromosomal regions containing genetic variants shared between unrelated people. If patients

with bipolar disorder are statistically more likely to share a particular gene variant with each other than they are with

people who do not have bipolar disorder, that gene variant may well play a role in disease onset or maintenance (and, if

it plays a part in neither, can still serve a predictive function). In short, while they are not yet conclusive, the linkage

scans referenced by Dr. Gershon have lent credibility to the hypothesis that bipolar disorder and schizophrenia may share

some genetic risk factors.

Shared Risk Factors

“Various researchers have performed genetic association studies, and a number of genes have been found—in

multiple reports—to be associated with both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia,” Dr. Gershon says. “That’s

good news for those of us trying to get to the bottom of these illnesses. However, despite implication of the same genes,

there hasn’t been much consistency in the specific alleles—that is, particular DNA sequences—these studies

have turned up.” As Dr. Gershon explains, the lack of specificity at the level of alleles is

a major challenge for researchers. “One possibility is that the genes that have been associated with bipolar disorder

and schizophrenia have multiple mutations, with different mutations appearing in some series.” The validity of this multiple mutation

hypothesis will only be uncovered by intensive sequencing of the implicated gene regions in very large numbers of individuals,

and it is just such large-scale sequencing studies that Dr. Gershon and his colleagues are calling for.

“We’d also like to conduct genome-wide association studies,” Dr. Gershon says. “Currently, that

means dealing with half a million markers, though that number may go up to a million over the next year or two, distributed

over the genome.” These markers were identified through the Human Genome Project, a world-wide collaboration of many

laboratories, funded by the NIH and other public bodies. They allow very dense examination of each chromosome for

illness-associated variants.

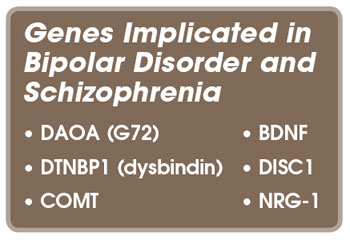

Genes and Gene Regions Implicated in Bipolar Disorder and Schizophrenia

“One region we’ve been especially interested in is the long arm of chromosome 13,” Dr. Gershon says.

The gene in that region that has been most associated with bipolar disorder and schizophrenia is actually, and somewhat

confusingly, called by several different names. Originally it was named G 72, but in later lab experiments it was found

to inhibit the enzyme D-amino-acid oxidase (DAO), so this gene is officially now known as DAOA, short for ‘D-amino-oxidase

activator.’ “There’s also a gene, VGCNL1, in the vicinity of DAOA that appears very promising,” Dr.

Gershon says. “It’s come up in genome-wide association studies, and has also come up positive in a number of

our intensive studies of genes in this general region. It is possible that more than one gene in the region contributes

to illness susceptibility.”

Dr. Gershon also names neuregulin-1 (NRG-1), another gene abnormality currently under close scrutiny for its possible

role in schizophrenia. “NRG-1 first came up first in study from Iceland, and has since been implicated in other studies

as well,” Dr. Gershon says. “NRG-1 appears to be significantly over-expressed in the prefrontal cortex and

the hippocampus of those with schizophrenia; interestingly, both the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus are involved in

higher cognitive processes.” The gene encoding the protein dysbyndin-1 has also been implicated in schizophrenia,

and appears to be linked to susceptibility

to the disorder.

“DAOA is strongly implicated in both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia,” Dr. Gershon says. “There is

some evidence that NRG-1 might overpresent in individuals with bipolar disorder, but they’re not conclusive. The

dysbindin-1 encoding gene appears to be implicated mainly in schizophrenia.” Other genes that may be associated with

both illnesses include COMT, BDNF, and DISC1.

“The overlap in genetic susceptibility is quite interesting,” Dr. Gershon says.

“It appears that, although they tend to run in different families, both bipolar disorder and schizophrenia may share

some common genetic—and therefore biologic—susceptibilities. This may partly explain why the two disorder have

shared symptoms and respond to some of the same medications.”

Treatment

“Our hope is that identifying susceptibility genes will lead to new molecular targets for drugs, producing completely

new treatments, some of which might well be more effective than those currently available,” Dr. Gershon says. Currently,

researchers have identified genes implicated in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia, but they have yet to determine which

variants of these genes are responsible for the disorders. “Before we discover new treatment targets it’s likely

that treatment will be positively impacted by studies of genetic susceptibility to treatment side effects,” Dr. Gershon

explains. “For example, the dopamine receptor gene DRD3 has been associated with tardive dyskinesia,

a serious side-effect of some older antipsychotic drugs. The ability to predict patient response to treatment before prescription

would be an enormous boon.”

Conclusion

“The answers we’re currently seeking are going to come from big science,” Dr. Gershon says. “Laboratory

costs are coming down, but we need huge studies to pinpoint the genetic variants that are of most importance in diagnosing

and treating bipolar disorder and schizophrenia.” While Dr. Gershon stresses that the speed of progress is going

to depend largely on how much money is put into funding these studies, he is confident that results aren’t far off. “Clinicians

should be in a state of watchful waiting. We don’t have the information they need to improve treatment quite yet,

but it’s coming. The ability to predict treatment response, in particular, is close, and the identification of new

targets for treatment is not far behind.”

Disclosure: Dr. Gershon has a financial relationship with Epix Pharmaceuticals.